What different messages were intended by the color choices of pharaoh’s various lappet wigs? These distinctive wigs, which appear in numerous variations, were adorned with a spectrum of colors–not only black, like the wigs worn by the king’s subjects, but also bright blue, red, and even white. What did these colors add to the significance of the king’s costume, and what was their impact on context? In the first entry in this series, I outlined the history of this wig type and discussed its varied shapes. This article will examine the colors used for the lappet wig worn by the king and briefly describe the significance of each hue to the ancient Egyptians in an effort to deepen the understanding of the meaning conveyed by this royal headgear.

Royal wigs are very often depicted as being black. This likely refers to what was the actual color of almost all wigs–the lappet wig was certainly the most ‘democratic’ of the king’s headgear and may have been worn specifically to emphasize his humanity. However, black also carried heavy connotations of fecundity and had deep primordial connections as well. The color was closely associated with the Netherworld and death in addition to the resurrection of Osiris and fertility (G. Pinch, “Red Things: the symbolism of colour in magic,” in W.V. Davies (ed.), Colour and Painting in Ancient Egypt, (London, 2001), 183). The connection of the color to fecundity was likely related to the rich Nile silt deposited on the ‘black lands’ with each annual flood (Noted, for example, by R. Wilkinson, Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art, (London, 1994), 109.). Probably due to this relationship with the fertile soil, black could also carry all the positive symbolic significance of green, the color of growing things and life itself. Doing ‘green things’ (positive behavior) was often contrasted by ‘red things’ (evil), suggesting yet another level of significance to the opposition of black and red. Osiris, embodying the rich silt and as the epitome of the chthonic dark mass of potentiality, is often shown with either green or black skin.

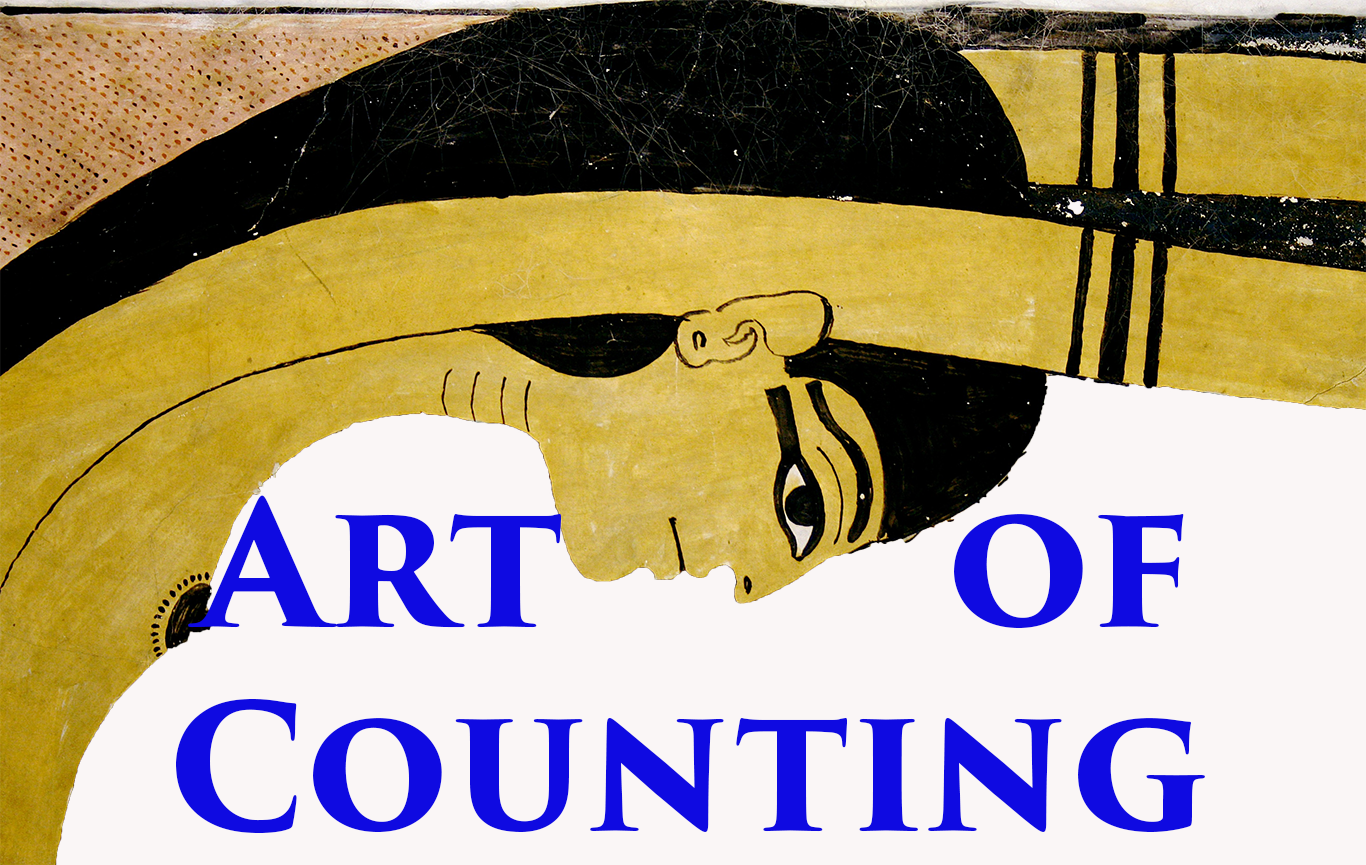

Section of the Litany of Re in the tomb of Ramses III (KV 11) showing some of the 75 nocturnal forms of the sun god, including one called ‘Kheperer’. This is the dormant sun god of dawn who during the night was entirely black with a head like a scarab beetle, representative of the endless potential and inevitable spark of creation manifested in this being:

Even when worn by pharaoh, the color of a black wig may be most often indicative of reality. However, black being intimately linked to both vegetal decay and the rich silt deposited by the annual flood that renewed the land, this color also carried significant connotations related to the cyclical nature of the cosmos.

Detail of Ramses III in his tomb (KV 11) wearing a black lappet wig:

Many of the examples at Medinet Habu are sadly stripped of paint, but there are a few where color can be postulated. These include the scene recorded in the Oriental Institute’s Epigraphic Survey of Medinet Habu plate 99, which shows the king presenting spoil from the Libyan and Asiatic campaigns to the Theban Triad. While the level of preservation makes it somewhat uncertain, it appears from photographs captured during my research season that the king’s wig was painted black here.

General view of king and prisoners in scene of plate MH 99, within context of the north wall of the first courtyard:

Detail of king from plate MH 99 scene showing dark edges and traces of black paint at crown of head:

The wig in Medinet Habu plate 123B (the southeast corner of the first courtyard, discussed in an earlier article on the red-looped sash) is almost completely lacking paint, though it appears to have been black originally. If so, the use of this color for the king’s lappet wig in this context is probably linked simultaneously to two concepts: the humanity of the king, and his role in the recurring regeneration of the earth.

General view of the southeast corner of the first courtyard (MH 123B):

Detail of king in MH 123B showing hints of black paint at back of head:

Royal wigs of all shapes are also commonly shown as dark blue. This color is a reference to lapis lazuli, often referred to as the stuff of which the hair of the gods is constructed. This indicates a connection between the wigs and the symbolism of that material as well as suggesting the divinity of the king when he dons the cobalt curls. Lapis was also associated with the night sky and the primordial waters, both dark masses of potentiality from which life springs at the divine spark of dawn. Similarly, the stone is connected with the virility of the Kamutef bull, which regenerates itself (For more on lapis, see: S. Aufrère, L’univers mineral dans la pensée égyptienne, (Cairo, 1991), esp. 481-82.).

Ramses wearing a bright blue round wig encircled by a seshed diadem in a ritual scene found in the western portico of the second courtyard (MH 287A):

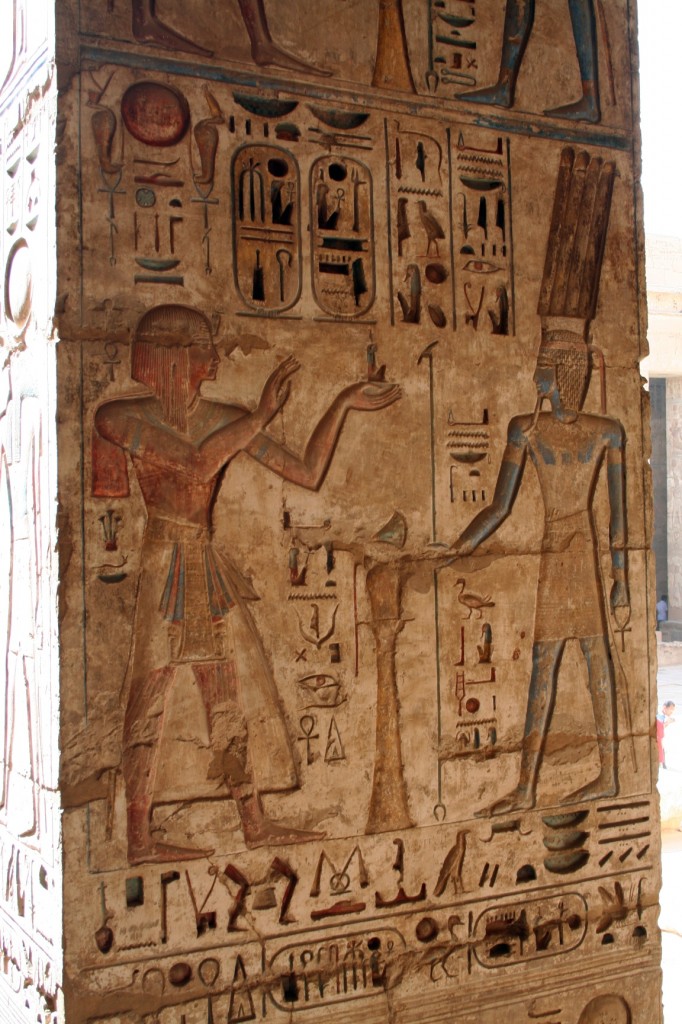

When the king wears a blue wig, the color is probably intended primarily to liken him to a god. There are a number of blue painted lappet wigs preserved in the temple of Seti I at Abydos, although the wig is relatively uncommon here and it should be noted that there was a distinct avoidance of the use of black in this temple (discussed by John Baines in “Color use and the distribution of relief and painting in the Temple of Sety I at Abydos,” in Davies (ed.), esp. 149). Several of these examples were illustrated in the first installment on this topic, all of which depict the king receiving insignia or divine emblems. Another example, in the Horus chapel of the Osiris complex, shows the king in a blue lappet wig offering incense and libation to Osiris and Isis. Pharaoh also wears a red looped sash in this instance (Calverley and Broome (1936) vol. 3, pl. 34).

Seti I presenting incense and a libation to Osiris and Isis while wearing a blue lappet wig and red looped sash:

In certain contexts, the use of blue may be indicative not only of divinity but could carry additional, more cosmic, significance, especially given blue’s relationship with the formless masses and their creative potential. A more thorough statistical examination of the specific appearances of this wig color would be required to quantify any such connections with certain types of scenes.

In addition to black and blue, the lappet wig appears in particular contexts as red. As an earlier article investigating the significance of red in ancient Egypt demonstrated, this color is the most ambivalent of the ones discussed here. Red, far more than blue, white, or even black, was viewed as being potentially chaotic and dangerous in addition to having positive associations, such as with solar intensity and rebirth. Red was the color of the fiery weapon of the Eye goddesses who protected the sun god on his perilous journey, but it was also the color often used for depictions of their primary foe–the chaos serpent, Apep. Potentially problematic sections of text were written in red to control them, while the dresses of certain apotropaic goddesses were described and depicted as being made of bright red linen. One thing is certain–red was considered to be potent and very powerful.

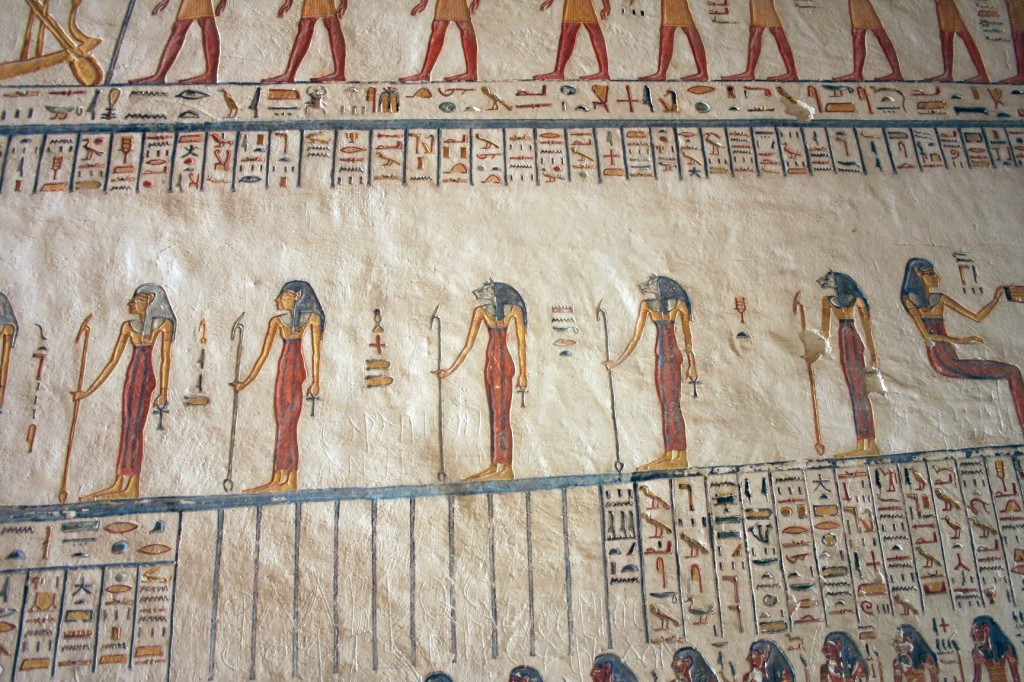

Guardians of the sun god (in KV 9) dressed in bright red linen:

In the tomb of Khaemwaset (QV 44), Ramses III processes before his son, offering incense, while wearing a red lappet wig, a feathered back apron, a panther at the top of his apron, and a red looped sash.

Ramses III in his son’s tomb (QV 44) wearing a red lappet wig:

Detail of the king’s kilt in the above scene in QV 44 showing the tiny leopard skin at the top of the multiple apron, feathered back apron, and pair of jackal heads at the points of his triangular kilt:

Another example of the king wearing a red lappet wig comes from the tomb of Amunherkhepchef (QV 55). Again, the king also wears a multiple apron with a panther at the top and a feathered back apron. The use of red suggests a strong solar aspect to the king’s costume, and this would be supported by the rest of the regalia, such as the multiple apron, the panther head, and the appearance of the jackal heads at the tip of his pointed kilt, perhaps connected to the jackals that tow the solar bark.

Jackals on the astronomical ceiling in the burial chamber of KV 9:

Ramses III wearing a red lappet wig in his son’s tomb (QV 55):

Detail of the king’s kilt in the above scene in QV 55 showing the same elements as in the QV 44 scene depicted above:

Detail of jackal heads on the pointed kilt tips on one of Tutankhamun’s sentry statues:

At Medinet Habu, there are several examples of lappet wigs where it is unfortunately not possible to determine color. However, one certain red lappet wig appears on the king in the first courtyard. In MH 96, pharaoh is shown being presented with spoil from a Syrian campaign depicted in the lower register on the north wall. Preserved paint reveals that the king wore a bright red wig in this instance.

Ramses standing at his balustrade receiving spoil (MH 96):

Detail of the king in MH 96 showing the remains of bright red paint on his lappet wig:

Note that the king’s lappet wig also appears to be red in MH 19, a slaughter scene that shows the king in battle with the Libyans. This usage of a red wig in a slaughter scene suggests another level of significance. The color may be a reference to either ‘face’ of the solar Eye—the protective aspect or the aggressive aspect—depending on the context. If red in this scene, the color would likely indicate the protection of the fiery apotropaic Eye, especially since MH 19 is the only relief in the second courtyard that depicts aggressive foes.

Ramses III slaughtering foes from his chariot (MH 19):

Detail of the well-armored king in MH 19:

Detail of the king’s head in MH 19 showing red paint on his lappet wig:

Another red lappet wig appears in an offering scene found on a pillar in the west portico of the second courtyard (the is one of three lappet wigs depicted on these pillars–the other two are damaged and appear to have been black).

Ramses III offering Ma’at to Shu while wearing a red lappet wig (MH 281B2):

Detail of king in above scene (MH 281B2):

Almost all the lappet wigs depicted on Ramses III in the tombs of his sons (QV 42, 43, 44, and 55) are painted red, although the king also appears at least once in a black lappet wig—in QV 42.

Ramses III wearing a red lappet wig in his son’s tomb (QV 43):

Ramses III wearing a black lappet wig in his son’s tomb (QV 42):

In his own tomb (KV 11), Ramses consistently wears black lappet wigs.

Ramses III offering to Osiris and Isis in his tomb (KV 11):

Ramses wearing a black lappet wig within his tomb (KV 11):

Both black and red lappet wigs appear (worn with the looped sash) on pillars in the burial chamber of Ramses VI (KV 9).

Red and black lappet wigs appearing in the burial chamber of KV 9:

The looped sash also appears with the lappet wig in paired scenes from the tomb of Seti II (KV 15), on the back wall of the first columned hall above the descending corridor. The king twice faces Osiris and offers Ma’at while wearing a black lappet wig and wine wearing a white lappet wig.

Seti II wearing black and white lappet wigs in his tomb (KV 15):

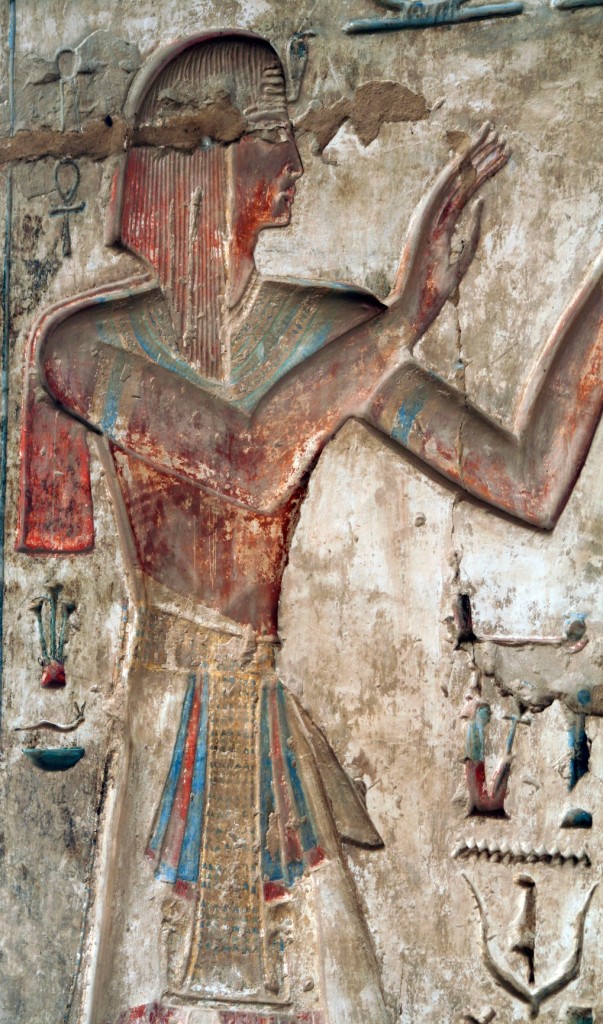

White was associated with luminosity, the moon, and silver. It was also closely related to ritual purity–priestly clothing is almost invariably white, and white sandals (here is a previous article on the significance of sandals) were required by the Books of the Dead before the deceased could recite the spells. Many of the sacred animals were white, including the ‘Great White’ baboon related to the lunar god Thoth. White was also the heraldic color of Upper Egypt, embodied in the king’s hedjet crown.

White crown (hedjet) worn by Ramses III in QV 44:

Another white royal headgear was the ambiguous khat headdress, which had ritual connotations as well as solar and funerary significance. One of the life-size bitumen covered sentry statues from the tomb of Tutankhamun wears the khat (JE 6070). While the pair statue wears the nemes, (another type of royal headcloth, usually shown with blue and gold horizontal stripes), neither are depicted with their usual coloration–both headdresses are gilded instead.

The khat is sometimes painted yellow as well; there are a number of instances in the Seti Abydos temple where the king wears a yellow khat.

Seti wearing a yellow khat while presenting an incense and libation offering to Isis:

However, the usual color for this headcloth when worn by the king is white.

Khat headdress worn by Ramses III in QV 44:

The hedjet crown and khat headdress are the only commonly occurring white royal headgear. The white lappet wig is extremely rare. The example in KV 15 is the only one of which I am currently aware, although please note that I have not yet made a thorough survey of the Ramesside royal tombs. Its use in the scene from Seti II’s tomb is likely intended to stand in particular contrast with the black lappet–to encompass the full spectrum of the most intense luminosity to the deepest dark of the Netherworld–and perhaps symbolically suggests the full solar cycle the king’s tomb was designed to support.

The royal lappet wig was depicted as being black, bright blue, intense red, or even pristine white. Now that we have briefly discussed the symbolism of these various colors in ancient Egypt and pointed out several occurrences of the different colored wigs in context, we will be able to examine the statistical results and findings from Medinet Habu within a broader framework. As mentioned above, much of Medinet Habu is unfortunately stripped of paint, particularly the outer walls where many of the battle scenes (and thus many of the lappet wigs) appear. The examples discussed above with color all come from within the two courtyards, but even in this space there are many wigs where color is very difficult to determine. From the surviving paint, however, it is clear that multiple lappet wig colors were used at Medinet Habu, so it is useful to discuss the potential significance of each and the different meanings that they would bring to the king’s costume within his context.

In the next and final installment of this series on the royal lappet wig, I will outline all the examples of this headgear at Medinet Habu, examine the results of the advanced statistical analyses applied to the data, and investigate what the appearance patterns of this royal attribute can reveal about the contextually relevant message communicated by the king’s costume. Don’t miss it!

What an interesting article fantastic photos i’m enjoying reading about different aspects of ancient Egyptian art. fantastic

Thanks for your great information,

It’s very helpful..

Excellent-so glad you found it helpful! Thank you very much.