(Sincerest thanks to Tom Hardwick for his astute comments and suggestions during the crafting of this two-part article)

You can tell a lot by the shoes someone wears.

Context clearly affects the choice of footwear; one pair for dancing, another for traffic court, and yet another for weeding the garden. The President might often wear either golf and dress shoes, but golf shoes would not be the choice for a visit to Congress, though golf shoes may be seen when he is simply with congressional leaders on the green. You should see what my husband wears most of the time.

As in 21st Century America, so in ancient Egypt: the context appears to have also influenced whether or not pharaoh was depicted wearing sandals, but the subtleties of their usage patterns have not been statistically analyzed. The Art of Counting sought to change that.

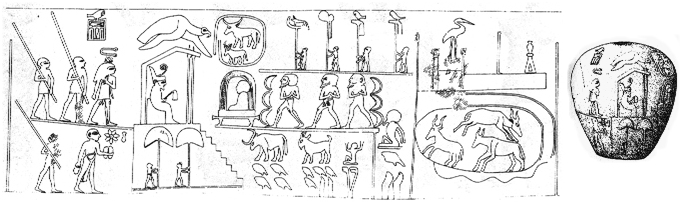

Sandals occur on some of the earliest pharaonic images. On both faces of the Narmer palette (c.3100 B.C.E.), for example, the king is shown barefoot but followed by his sandal-bearer.

Narmer palette (detail):

This same figure stands just behind the kiosk containing the enthroned king on the Narmer macehead, reinforcing the early importance placed on footwear.

Drawing of scene on Narmer macehead:

Like those officials who carried sunshades in association with the king, sandal-bearers were of very high status. Sandals themselves may have represented a symbol of relative status, meaning that when the king wore sandals they were intended to separate him from the people, since he was of much higher status, and from the gods in certain contexts, often those scenes where pharaoh was depicted as closely connected to the terrestrial realm. Examinations of Old Kingdom tomb relief have indicated that context could have played a larger role than social status in whether or not sandals were worn by the elites, and personal preference also influenced their usage. They were generally chosen for outdoor activities and, in a funerary context, may have been reflective of the ability of the deceased to leave the tomb.

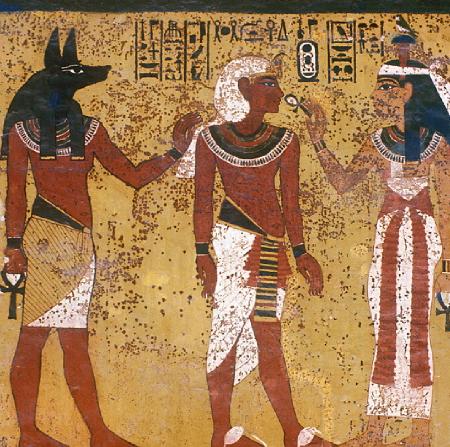

In addition to their understandably common and practical use for protecting the feet when walking or working outside, sandals were often connected to purity. For instance, the Book of the Dead 125 required the deceased to be ‘pure and clean…shod with white sandals’ before they could recite the spell. White sandals were used in ritual contexts, often being mentioned in the Netherworld literature as a necessary attribute of the righteous deceased. They were shown on the king’s feet in some late Eighteenth Dynasty tomb reliefs, such as the scene on the south wall of the tomb of Tutankhamun where pharaoh is depicted between Anubis and Hathor.

Tutankhamun between Anubis and Hathor wearing white sandals:

Tutankhamun had at least 42 pairs of sandals buried in his tomb with him.

Tutankhamun’s footwear as displayed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo:

Most of these are plain, but several are elaborately decorated. The embellishments are of two types. They either relate to the control of chaos (through bound prisoners, bows—representative of the Nine Bows, the traditional enemies of Egypt—and sema-tawy symbols, which show the binding together of the Two Lands of Egypt) or the decoration represents the result of the successful maintenance of cosmic balance (vegetal motifs, flowers, geese—all connected with the early manifestation of creation).

Tutankhamun’s sandal decorated with bound prisoners and sema-tawy symbols:

Tutankhamun’s sandals decorated with flowers and vegetation:

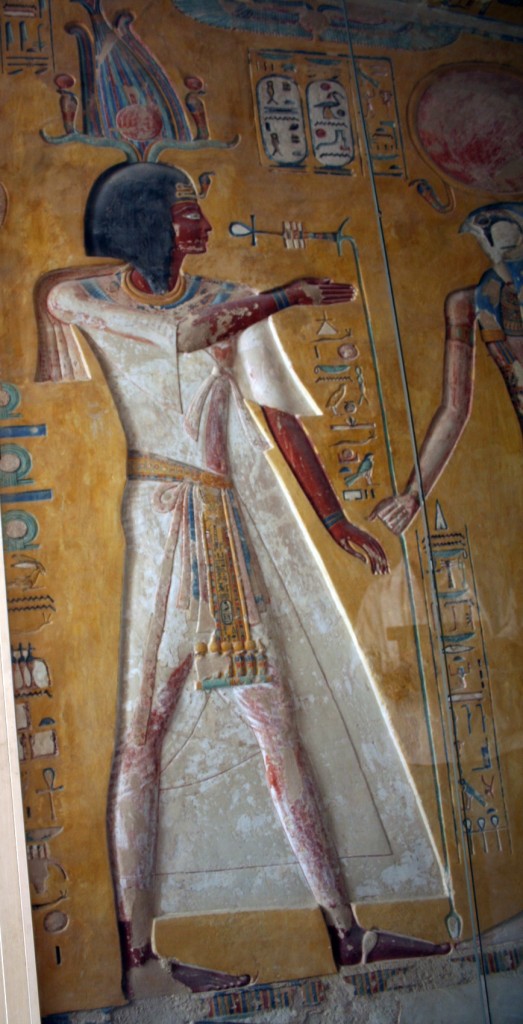

Sandals occur more regularly in Ramesside tombs, especially in the scenes connected with the Litany of Re that appear at the top of the first corridor.

Litany of Re opening scene in KV47:

Although they were used throughout Egypt’s history and in largely comprehensible contexts—physical protection and maintenance of ritual purity—the answers to specific questions about when, how, and why pharaoh was shown wearing sandals remained difficult to grasp.

In the initial stage of the Art of Counting project (my Ph.D. dissertation), I focused solely on the wall scenes found on the exterior and in the two courtyards at the memorial temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu. This dataset was comprised of 189 scenes and was examined as a collection primarily due to their ‘public’ nature—unlike the inner rooms of the temple proper, humans other than the king and select priests could have had limited access to these scenes.

The iconography appearing in these two large areas of the temple—the exterior walls and open courtyards versus the inner pillared halls and inner rooms—is also rather different. There are some scene types that overlap and appear in both areas of the temple, but there are a number of types and variables that only occur in one or the other. For the initial case study, the fundamental difference in the character of the scenes in the two sections suggested that one group would be more productively analyzed separated from the other to avoid skewing the statistical results. By analyzing discrete groups of ‘similar’ types, a baseline can be achieved for the usage patterns of variables within a given context. These results can then be compared with additional analyses applied to the larger dataset or to other selected groups, which can quickly highlight variations in the way attributes are used in different contexts.

At this point, all of the scenes at Medinet Habu recorded in the Oriental Institute’s epigraphic survey, save those that are extensively damaged, have been entered in the database—a total of 765 records. My analytical partner, Lili Garrard, was kind enough to recently run tetrachoric correlation analyses (see an earlier post for a simple explanation of correlation, and you can go here for a deeper dive into tetrachoric correlation) on two new datasets chosen from the Medinet Habu database—one that included all the 524 offering scenes and one focused on the 120 scenes found on the pillars in the second courtyard. A preliminary examination of these results revealed several interesting tendencies, such as the consistency with which the king offers the ‘clepsydra’ (a baboon seated on a nb basket) to female deities, most of which are specifically connected to the Eye. But we’ll discuss these and other results from the new analyses in future posts.

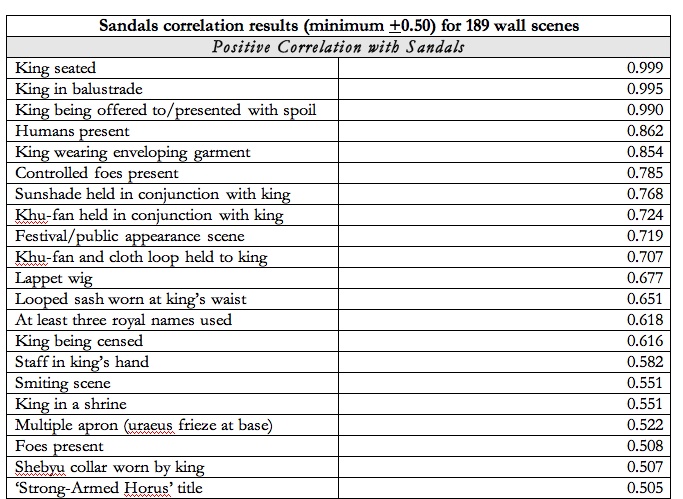

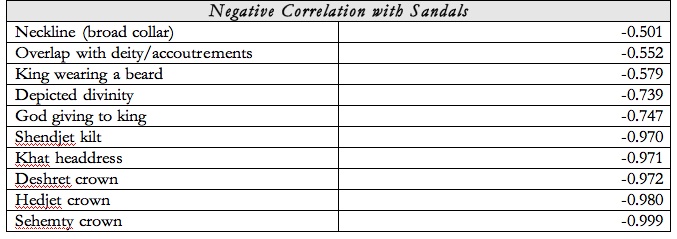

Within the selected dataset of 189 scenes used for my case study, the king wears sandals 51 times (27% of the scenes). A tetrachoric correlation analysis revealed some notable usage patterns for sandals within this dataset, as summarized by the table below.

The results from the tetrachoric correlation clearly indicate that sandals were not worn with the shendjet kilt, the sehemty (double) crown, or the khat headdress. The strong negative relationship between sandals and the beard also indicate that they were rarely worn along with the atef, nemes, round wig and seshed, or shwty since all of these headgear are always worn with the beard. In these scenes in the outer parts of the temple, sandals are usually not worn when there is a depicted divine presence, especially when a god is shown giving something to the king. There is a marked tendency for sandals to be worn with the shebiu collar rather than the broad collar (neckline).

At the positive end of the relationship scale, the sandals are worn in nearly all scenes where the king is depicted either seated or standing in a balustrade—the correlation with these venues is extremely high.

Ramses seated in his chariot being presented with spoil:

Ramses standing at a balustrade being presented with spoil:

They are chosen often for those scenes showing Ramses being censed as well as for many festival appearances. The lappet wig is the most closely correlated of the headgear, and it appears that the multiple apron was strongly preferred for occurrences when the pharaoh wore sandals.

Multiple apron worn with the sandals:

Fans of both types currently being tracked (sunshades and khu–ostrich plume fans) are closely connected to the sandals, as is the enveloping transparent garment. The king wore sandals in some smiting scenes and they were also chosen regularly for those scenes where at least three of his names were written in the name block.

Ramses smiting on back side of the Window of Appearance (note that there are also three royal names used in this scene):

I wondered how consistent these patterns would remain when the dataset was expanded to include all the scenes from Medinet Habu. In the expanded dataset, the king wears sandals in 129 (16.8%) of the 765 scenes, compared to 27% of the exterior and courtyard wall scenes selected for the dissertation. Although there are a few areas areas of divergence, many of the quantifiably indicated patterns remain strong. In the second part of this post on sandals, I will discuss the consistencies and differences between the findings of the two datasets.

And get ready, because the Art of Counting will present some strong statements (based on the data from Medinet Habu) on the meaning of the king’s sandals in Part II.

Amy,

You really are doing some fascinating work. Thanks for continuing to share this.

Brian

Thank you, Brian–I am delighted that you continue find this effort to be of interest. Your feedback is most appreciated!

Best,

Amy

An excellent piece of work and a great help , am researching Tuthmosis 3 attack on Megiddo

Thank you so much, John! Very glad the article was helpful–it is amazing what you find when you examine those reliefs. Good luck with your work!

Amy,

Do you have any images of Tuthmosis 3 wearing leather sandals on statues or wall carving?

Regards

John

Hi John,

Perhaps; will have to look in my photo library. I shot much of the small temple of Tuthmosis III & Hatshepsut at Medinet Habu, so may well have some. Will check and get back to you soon!

Best,

Amy

Your attention to detail in your photography is awesome. I develop an animated series deeply tied to ancient Egypt, with an element relating to sandals, specifically, so I know most of the stories that come what that. I’m surprised you didn’t include the story about Tut’s throne… are you aware of it?

In any case, I’ve been looking for some master quality reference for some of these hieroglyphs for awhile, so thank to you!

Thank you, David–glad that our work is helpful for you. I love to shoot details, and Egyptian monuments are simply packed with them. I am intimately familiar with Tutankhamun’s material, but not sure what story you are referring to. I’m intrigued!

I just happened across your website. Great work. Perhaps you can help me with the meaning of the rosette and jar? That accompany depictions of the sandal bearer in early dynastic representations. Are they phonetic symbols or names or ??

I will be reading your blog diligently in the next few days