While we may know what a lappet wig is, what does it mean? Among the headgear worn by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom is a particular wig that is short in the back and longer at the sides. This wig appears in a variety of configurations and shapes; some have long sides that fall past the shoulders, others are significantly shorter; some have layered rows of curls and others show smooth striations from the crown of the head to the ends. All of these variations seem to be largely interchangeable and fall under the general designation of ‘lappet wig’, clearly distinguished from the other type of wig worn by the king (often referred to as a ’round wig’), both by its physical appearance and the contexts in which it was used. Although this wig has received some attention from other scholars, the particular meaning of this royal headgear remains somewhat obscure. Using the Medinet Habu database and the statistical analyses performed on those data, the Art of Counting project will further clarify the specific significance of the lappet wig and help identify the reasons it was worn by pharaoh in certain contexts. In this series, in addition to examining the wig’s common use in battle and for violent action, we will also aim to illuminate why it was chosen for particular types of offering scenes and how it fits into funerary contexts as well.

Detail of Ramses III wearing a lappet wig at Medinet Habu:

The lappet wig appears in 73 of the 765 scenes at Medinet Habu. It was chosen for:

- 39 depictions of the king presenting an offering to the gods

- nine scenes where the king processes

- seven scenes of slaughter

- seven scenes from the interior of the East High Gate where he interacts with young females

- five scenes where he is presented with spoil on the battlefield

- four iconic smiting scenes

- one scene where he receives ‘life’ from Amun

- one found in the royal mortuary complex where the king addresses an enshrined Osiris

Before delving into the particular appearances at Medinet Habu, a brief examination of the history of the lappet wig is prudent. The development of this wig during the New Kingdom is somewhat unclear. A wig with a diagonal edge running from the back of the head down towards the front resulting in a short pointed lappet appears first on the king during the reign of Amenhotep II (K. Mysliwiec, Le portrait royal dans le bas–relief du Nouvel Empire (1976), figs. 101-105). A depiction from the tomb of Kenamun (TT 93) of a cult statue of the pharaoh as a Nubian commander shows him wearing the military costume of the region, including a cut leather apron and the short, valanced wig (C. Aldred, “Hairstyles and History,” BMMA 15.6 (1957), 142. N. de G. Davies, The Tomb of Ken-Amun at Thebes, (New York, 1930), pl. 11). This is also one of the earliest appearances of the shebyu-collar (See P. Brand, “The Shebyu-collar in the New Kingdom, part 1,” JSSEA 33 (2006), 22).

Statue of Amenhotep II as a Nubian commander, tomb of Kenamun (after Aldred):

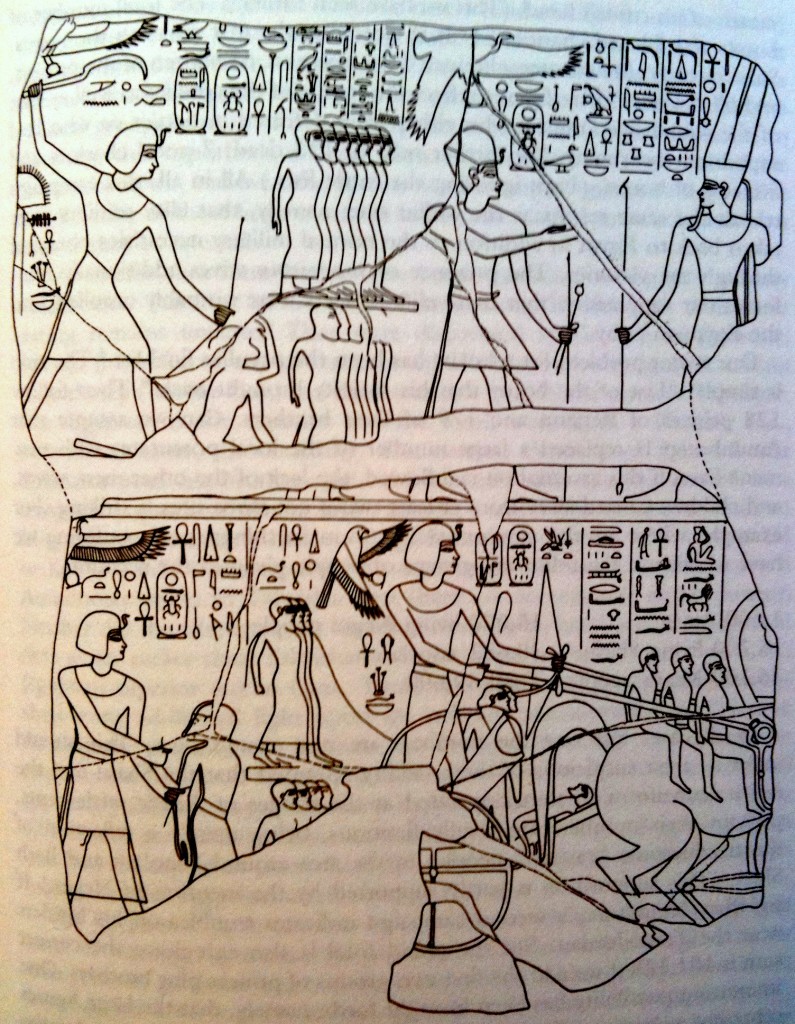

Fragments of battle relief from the same reign, now in Cairo (JE 36360), show the king wearing this wig in three of the four depictions—one of the king smiting, one showing him binding foes, and the last presenting him in his chariot returning in triumph (A-H. Zayed,, “Une representation inédite des campagnes d’Aménophis II,” in Posener-Kriéger (ed.), Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar I, (Cairo, IFAO, 1985), pl. II). Amenhotep wears the khepresh crown in the remaining vignette, which shows him before Amun-Re.

Battle scenes of Amenhotep II (after A. Spalinger, War in Ancient Egypt , fig. 9.2):

The king also wears this wig in his jubilee temple at Karnak, where it is topped with a horned crown. The diagonal edge of the wig is embellished with several rows of curls, much like those seen on some lappet wigs at Medinet Habu, but it is significantly shorter and does not have lappets that hang over the shoulders.

Amenhotep II on a pillar in his jubilee temple at Karnak (after Mysliwiec, fig. 102):

Although this wig is generally considered to be unrelated to the lappet wig worn by the Ramesside pharaohs, the data suggests that it is functionally connected. For instance, like the later lappet wig, the ‘Nubian’ wig was worn in battle scenes, as Amenhotep II does in his reliefs from Karnak and also in the well-known scene of this pharaoh firing arrows into copper ingots.

Amenhotep II firing into copper ingots (after I. Shaw and P. Nicholson, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, p. 113):

Also like the lappet wig, the ‘Nubian’ wig was sometimes topped with other headgear, as seen in the above depiction from Amenhotep II’s Karnak structure and in several other examples, such as on Horemhab in the court between the ninth and tenth pylons.

Horemhab wearing a ‘Nubian’ wig topped with an atef crown at Karnak (after Mysliwiec, fig. 201):

Later in the Eighteenth Dynasty, Tutankhamun wears this same wig when he presents bouquets to Amun and Amunet as part of the Opet festival (Epigraphic Survey, Reliefs and Inscriptions at Luxor Temple, vol. 1: The Festival Procession of Opet in the Collonade Hall, OIP 112 (Chicago, 1994), pl. 54.), and the king wears it on the small golden shrine from his tomb in five of the scenes, including one where Ankhesenamun presents him with bouquets (M. Eaton-Krauss and E. Graefe, The Small Golden Shrine from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (1985) pl. AR 8). He also wears a heavily pleated over garment and sandals in this instance. The other scenes on the small golden shrine where he wears the ‘Nubian’ wig suggest that it was especially connected to terrestrial and legitimizing actions. One of the scenes shows him grasping a rekhyet bird (representative of his subjects), another depicts him being led, and a third shows the king holding a crook while Ankhesenamun shakes a sistrum and a menat before him (Ibid., AR 1, AR 3, and CR 1).

Tutankhamun wearing the ‘Nubian’ wig on the golden shrine:

Like the fifth scene on the small golden shrine, where he sports the ‘Nubian’ wig and hunts birds (BR 3), the other depictions of Tutankhamun wearing this wig are scenes of violent action.

Tutankhamun hunting birds on the golden shrine (after T.G.H. James, Tutankhamun):

Two objects, a sunshade (JE 62001) and a bowcase (JE 61502), show him hunting in his chariot.

Detail of sunshade showing Tutankhamun wearing the ‘Nubian’ wig while hunting ostriches (after T.G.H. James, Tutankhamun):

One of the elaborate openwork buckles (JE 87847) depicts him driving captives before his chariot, and one of the ceremonial shields (JE 61576) also shows him wearing this wig while he smites two lions grasped by the tails. In this last example, the wig is encircled by a seshed diadem and topped with a shwty crown.

Tutankhamun’s shield:

Perhaps the most persuasive example for the idea that the ‘Nubian’ wig and lappet wig are conceptually similar comes from the temple of Seti I at Abydos. Seti wears the lappet wig quite often in this temple and elsewhere, but there is one scene in the chapel of Seti where he sports the short pointed wig instead (A. Calverley and Broome, The Temple of Sethos I at Abydos, (London,1935), vol. 2, pl. 35). This scene depicts not the living king but a statue of him, striding and holding a staff, placed beneath the bark of the deified king.

Drawing of Seti I statue wearing ‘Nubian’ wig (after Calverley and Broome):

Detail photograph of the Seti I statue:

As the numerous Ramesside examples (mentioned in the following discussion) indicate, the lappet wig was often chosen for this type of statuary. The fact that this relief depiction of a royal statue shows the king wearing the short ‘Nubian’ wig instead supports a parallelism between them.

Since the pointed ‘Nubian’ wig was worn so regularly at Amarna, this particular wig shape likely became intimately connected with the ‘heretic’ rulers, particularly the royal women.

Detail of the back of Tutankhamun’s golden throne showing Ankhesenamun wearing the ‘Nubian’ wig (Tuankhamun wears the ’round’ wig topped with an elaborate hmhm crown) (after T.G.H. James, Tutankhamun):

After the demise of Akhenaten and the end of the Amarna era, the ‘Nubian’ wig shape was largely discarded, although it does appear occasionally. Besides the example of Seti I at Abydos, Ramses II also wears the ‘Nubian’ wig in a slaughter scene at his temple at Beit el-Wali.

Ramses II wearing the ‘Nubian’ wig at Beit el-Wali (after T.G.H. James, Ramses II, p. 173):

After the Amarna period, instead of the ‘Nubian’ wig a previously non-royal wig with the longer, rounded lappets began to be worn by the king. Wigs with long lappets and rows of curls (sometimes called ‘double’ wigs) were commonly worn by elite men and military personnel in the mid-late Eighteenth Dynasty; see, for example, the head of an elite male from the reign of Amenhotep III (in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MMA 25.4).

It is probably because of the military relationship with the lappet wig shape that it becomes so prominent under the Ramesside pharaohs. In examining battle relief and military depictions through the period, it becomes clear that there were numerous variations of this wig type worn by members of the Egyptian army, and it seems likely that the different wig shapes and lappet lengths indicated various ranks or classes of soldiers (P. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I and their Historical Significance: Epigraphic, Art Historical and Historical Significance, Ph. D. dissertation, University of Toronto (1998), 25). Late in the Eighteenth Dynasty, a wig with lappets appears in several variations in the tomb of the general Horemhab at Memphis (such as on the pilasters, now in the British Museum (EA 550 and 552)

Symbolically, the functions of the ‘Nubian’ wig and lappet wig are consistent. Both of the wigs are used extensively in battle and scenes of violent actions. They are also both worn in scenes where pharaoh is shown offering revivifying bouquets or legitimizing Ma’at (symbolic of cosmic order). These two contexts present flip sides of the same royal function. In the slaughter scenes, the king actively controls chaos, like Seth raging on the prow of the solar bark, while the offering scenes depict pharaoh presenting to the gods the tangible results of his success keeping isfet (chaos) at bay.

Both the ‘Nubian’ and later lappet wig are unusually democratic types of headgear—pharaoh was certainly the only human who wore the atef crown, but anyone could wear a wig. When pharaoh wears a wig, an intentional effort may be being made to humanize him to a certain degree, perhaps emphasizing his mortality. Different wig types and shapes likely indicated aspects of economic and social status, but there is little argument that both the ‘Nubian’ and lappet wig shapes were used by the military. The wig, being lightweight and streamlined in form, was well suited to battle, especially to chariot warfare. The only other crown that regularly appears in battle scenes, the khepresh, is also tight fitting and aerodynamic. However, the wig is not restricted to military usage.

A wig with long lappets, similar to those worn by Horemhab the general, is worn posthumously by Ramses I at Abydos, in a chapel dedicated to that king and constructed by his son, Seti I. Seti I also wears it topped with an atef on the façade of the same chapel, where he addresses his father and welcomes him to his ‘Mansion of Justification’ (G. Haeny, “New Kingdom Mortuary Temples and Mansions of Millions of Years,” in Shafer (ed.) (1997), 113-14).

Seti wears the lappet wig at least 29 times in his temple at Abydos, including several times where he offers bouquets and on multiple occasions where he is shown receiving vivifying elements or attributes of kingship (Calverley and Broome, (1936), vol. 3, pl. 4, 12, 22, and 26, for a few examples offering bouquets, and vol. 4, pl. 9, 14, 20, and 26 for a few of Seti receiving insignia or divine attributes.).

Seti I at Abydos wearing the lappet wig while grasping a rekhyet bird:

Seti I at Abydos wearing the lappet wig while receiving ‘life’ and ‘dominion’:

Seti I at Abydos wearing the lappet wig while receiving ‘life’:

Seti I at Abydos wearing the lappet wig while grasping a crook:

Seti I at Abydos wearing the lappet wig and being led by Montu and Atum:

In his battle reliefs at Karnak, Seti I wears the lappet wig eight times in the nineteen battle scenes, as opposed to six times where the king wears the khepresh. The wig is worn in four of the seven scenes of slaughter, while the khepresh is worn once (two scenes are too damaged to determine headgear). Ramses II also dons this wig in several instances, such as a battle scene from Luxor Temple that shows the king raging in battle, although he wears it far less often than Seti I did (Brand (1998), 24).

Ramses II wearing the lappet wig in battle at Luxor Temple:

In one of many existing examples showing the king wearing the wig while performing violent action on behalf of Egypt, Ramses II sports both the lappet wig and a looped sash on the south wall of the first hall at Abu Simbel where he tramples and spears prisoners.

Ramses wearing a lappet wig while trampling foes at Abu Simbel (after T.G.H. James, Ramses II):

As mentioned above, the lappet wig was worn regularly by Seti in his battle reliefs at Karnak. It appears in over half of the slaughter scenes (paired with the looped sash three times), for some of the depictions of his return in triumph, and once, again paired with the looped sash, when he presents spoil to the gods (Epigraphic Survey, The Battle Reliefs of King Sety I, OIP 107 (1986), pl. 3, 5, 6,12, 29, 32, 34, and 35.). Flabella, carried in the hands of personified emblems, appear behind the king in five of the slaughter scenes. The wig is also used for two scenes on the portal into the hypostyle hall, one where he offers bouquets to Amun-Re and Weret-Hekaw and one where he presents Ma’at to Re-Horakhty (Ibid., pl. 19C and 20B.). On the walls of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, the lappet wig is worn in eight instances when Seti I or Ramses II is shown being led by the gods or receives regalia elements (Epigraphic Survey, The Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, volume 1, part 1, OIP 106 (Chicago, 1981), pl. 7, 62, 106, 111, 121,149, 187, and 199.).

In his monuments at Karnak, Ramses III utilizes the target attribute a number of times and in ways that largely coincide with the proposed model of significance. The lappet wig is worn 23 times, with five of these occasions being related to battle cycles. Many of the others depict the king receiving ‘life’ and jubilees, while the remaining examples show him offering incense, ointment, or vegetation. Two similar scenes, found just inside the main entrance to his temple, show the king wearing a lappet wig and grasping the crook and flail while he receives emblems of rulership and jubilees from an enthroned Amun-Re (Epigraphic Survey, Ramses III’s Temple within the Great Inclosure of Amun, part 1, OIP 25 (1936) pl. 10 and 11.). The lappet wig and looped sash are combined twice on this monument, both times in scenes of slaughter. Sandals are also worn in one of these depictions.

Ramses wearing the lappet wig and receiving emblems of rulership from Amun-Re:

This wig appears on a standard-bearing statue of Ramses III found in the Karnak Cachette in 1904 (B. Mojsov, The Sculpture and Relief of Ramesses III, Ph.D. dissertation, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU (1992), 151.). This grey granite life-size image, which is now in Cairo (CG 42150), holds a ram-headed staff and according to the text was likely dedicated in Karnak at the annual festival of Amun (Ibid., 153). B. Mojsov refers to the headgear as a ‘civil’ wig, and notes that it also appears on other statuary of Ramses III as well as in relief at Medinet Habu (Ibid., 166).

Standard-bearer statue of Ramses III wearing the lappet wig:

The wig also occurs on an image of the enthroned sovereign, found at his temple in Beth Shan and now in Jerusalem, Rockefeller Archaeological Museum (PAM 2). In relief, the wig is depicted in a number of different variations, sometimes with striations running smoothly from the crown of the head to the bottom edge of the wig (like all of the Seti I Abydos examples illustrated above) while many instances at Medinet Habu appear to be a layered or ‘double’ wig, with eschelloned curls emerging from beneath a smooth top layer. Mojsov records that this type of layered wig is worn on a granite head with inlaid eyes found at Abydos (Cairo, CG 599). She identifies the head as Ramses III based partly on the unusual double wig, which she states is “found only on representations of Ramesses III.” (Ibid. 204).

Head of Ramses III from Abydos:

Different variations of lappet wigs appear on statuary of other Ramesside pharaohs, such as Seti I, Seti II, Ramses VI, and Ramses VII (Ibid., 154. Seti I (Cairo CG 751), Seti II (London BM 616), Ramses VI (Marseille 209), and Ramses VII (Cairo JE 37595). Below are three such examples at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Ramesside standard-bearer statue wearing the lappet wig (Cairo Museum):

Ramesside standard-bearer statue wearing the lappet wig (Cairo Museum):

Ramesside standard-bearer statue wearing the lappet wig (Cairo Museum):

The numerous variations in the specific shapes of these wigs is notable. Although they are almost universally short in the back, the lappets of the wig are often long and fall onto the shoulders. Regardless of their length, the ends of these lappets tend to be rounded, but pointed ends are also evident. Sometimes, the ends of the lappets almost mimic the shape of the lappets on a nemes headdress. As mentioned above, it is not only the shape that varies, but the way the hair is rendered as well. Some examples show even striations that extend from the crown of the head to the ends of the lappet while others present a more stepped profile, with rows of intricate curls emerging from below the smooth upper wig. The differences between these various manners in which the lappet wig is rendered may suggest some subtle variations in significance. However, more data would be necessary to proceed along that path.

This investigation of the development of the lappet wig worn by the king has highlighted the similarities between the usage of this wig and the earlier ‘Nubian’ wig, suggesting that they were considered to be functionally and conceptually similar. The prominent usage of the ‘Nubian’ wig during the Amarna period, especially by the royal women, suggests the reason that this wig shape was largely discarded as royal headgear after their demise–with this wig’s connection to the ‘heretic’ kings, it quickly fell out of favor in the Ramesside period. However, by this point the significance of the ‘Nubian’ wig, established by Amenhotep II, apparently made it an essential enough part of the king’s costume for particular contexts that it could not simply be discarded. An appropriate substitute was required. Given the nature of the Ramesside pharaohs–Ramses I was a general under Horemhab (who had also been a general)–it is not surprising that another military wig was chosen to fill this gap.

In the next installment of this examination of the lappet wig, we will discuss the various depicted colors of the wig–black, blue, red, and white–and examine the significance behind these choices. Then, the appearances of the lappet wig at Medinet Habu will be extensively discussed in an effort to illuminate the particular meaning held by this royal headgear and the reasons for its usage in various contexts.

The use of statistical analysis of ancient Egyptian bodily attire is growing more common as a means of understanding its development and reasons behind the wearing of certain elements and types. However, what I found strange in these series of articles is that the corpus of palaeoethnotrichological literature seems to have been ignored, and as such several different types of hairstyles with different historical lineages have been grouped together (e.g. the shoulder-length bob, duplex and Nubian or feathered hairstyle) favouring to categorise the hairstyle by its outline shape rather than its internal details. Although by Dynasty 19 these were all generally mid-length hairstyles I feel that if the accepted terms for the different hairstyles were used a more accurate reflection of their usage in certain rituals and scenes would result rather than the generic usage of mid-length hairstyles. The failure to use any of the literature on ancient Egyptian hairstyles means that rather than standing on the shoulders of giants, the author is starting from a hole and trying to reinvent the wheel. Several key works on hair include: E Dziobek, T Schneyer & N Semmelbauer Eine ikonographische Datierungsmethode für thebanische Wandmalereien der 18. Dynastie (Heidelberg 1992); AJ Fletcher Hair, in: PT Nicholson & I Shaw (eds): Ancient Egyptian materials and technologies (Cambridge 2000) 495-501; AJ Fletcher Ancient Egyptian wigs and hairstyles, Ostracon: Journal of the Egyptian Study Society 13(2) (2002) 2-8; AJ Fletcher The decorated body in ancient Egypt: hairstyles, cosmetics and tattoos, in: L Cleland, M Harlow & L Llewellyn-Jones (eds): The clothed body in the ancient world (Oxford 2005) 3-13; J Haynes The development of women’s hairstyles of Dynasty Eighteen, JSSEA 8 (1) (1977) 18-24; C Müller Friseur, LÄ II (1977) 331-332; C Müller Haar, LÄ II (1977) 924; C Müller Jugendlocke, LÄ III (1980) 273-274; C Müller Kahlköpfigkeit, LÄ III (1980) 291-292; C Müller Perücke, LÄ IV (1982) 988-989; C Müller Salbkegel, LÄ V (1984) 366-367; G Robins Hair and the construction of identity in ancient Egypt, c 1480-1350 BC, JARCE 36 (1999) 55; GJ Tassie Ancient Egyptian wigs in the Cairo and other museums, in: M Eldamaty & M Trad (eds): Egyptian museum collections around the World II (Cairo, 2002) 1141-1153; GJ Tassie People and technology used in creating ancient Egyptian hairstyles and wigs, in: H Selin (ed): Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-Western cultures (New York 2008) 1047-1052; GJ Tassie Hairstyling technology and techniques used in ancient Egypt, in Id 1052-1059; GJ Tassie The alchemy used by ancient Egyptian hairstylists, in Id 1043-1047; GJ Tassie The hairstyles represented on the Salakhana Stelae, in T DuQuesne (ed.) The Salakhana Trove: Votive Stelae and Other Objects from Asyut (London, 2009) 459-536; GJ Tassie What your hair says about you: changes in hairstyles as an indicator of state formation processes, in: R Friedman & L McNamara (eds): Egypt at its Origins 3: Proceedings of the International Conference Origin of the State. Predynastic to Early Dynastic Egypt, London (UK), 27 July-1 August 2008 (Leuven, in press), and also several theses: AJ Fletcher Ancient Egyptian hair: A study in style, form and function, unpublished PhD thesis (Manchester 1995); C Kriesel Altagyptische Haar- und Barttrachten, Unpublished Diplomarbeit (Leipzig 1958); C Müller Die Frauenfrisur im Alten Ägypten, Unpublished Dissertation (Leipzig 1960); GJ Tassie The social and ritual contextualisation of ancient Egyptian hair and hairstyles from the Protodynastic to the end of the Old Kingdom, unpublished PhD thesis (London 2008). If the author would like a full bibliography on ancient Egyptian hair and hairstyles I can provide her with one so that the vast amount of data can be more effectively interpreted.

Dear Dr. Tassie,

Thank you very much for your thoughtful and insightful comments. I greatly appreciate your input and considerations. Before going into detail below, let me say that I agree with you completely; there are more variables that need to be tracked and analyzed. The reasons that they have not yet been analyzed are explained below.

Let me begin by saying that I did in fact consult many of the references you point out (LA, Robins, Fletcher, some of your own articles—I’d love to see your dissertation, will it be published soon?—as well as Lohwasser, Aldred, Brand, etc.) for the small section of my dissertation where I discussed these wigs (which is from whence the text for this article series is derived). It was certainly not my aim to reinvent anything, but much of what I read was more concerned with wigs in general, their use in social identity, and construction technologies, etc., rather than with the specific uses of royal wigs. My approach was a broad spectrum study of Medinet Habu across a wide range of variables, albeit with a focus on regalia variables. My interpretation of the wig material is obviously not as refined as yours would be since it is one of your areas of specialty; my goal was primarily to provide a framework for the data from Medinet Habu through a survey of the appearances of these wigs in royal monuments.

While it may very well be the case that internal details are the most significant indicators of usage, at Medinet Habu at least I can say for certain that the ’round’ wig and ‘lappet’ wig in general are used in vastly different contexts. This is why I examined them in this baseline effort as two large groups of headgear—the data makes it quite clear that they were considered to be so. You are obviously correct about the many variations these wigs appear in. There is also a lot of variation in the internal details in the king’s wigs at Medinet Habu, but for my initial foray in this project I had to choose how much detail to track, and those many variations added a problematic level of separation at this stage for statistical analyses. Breaking the two large groups apart into the smaller components at this stage would have been inefficient and provided confusing statistical results with the sample size limitations. Future investigations could separate these details and identify subtle usage patterns related to the different internal details.

The reason why such analysis has not yet been done is because we have not reached the necessary sample size to make tracking such minutia useful. The planned expansion of our database, which will include material from many other monuments and from a significantly wider date range, will allow for more detailed variables to capture a broader spectrum of variations within larger groups.

You have also brought up a very important point that the Art of Counting project has already considered writing an article about, but hadn’t to date. Your comment shows that we have failed to elaborate on why there are stepped stopping points in this statistical process, how the selection process for variables works, and why certain analyses have not been performed. Thank you for pointing this deficiency out—it will be remedied shortly. Hopefully, this reply has helped to alleviate your concerns and explain our approach, but please do not hesitate to let me know if you have any other questions or comments.

I would be absolutely delighted to have your full bibliography on hair! Through your focus on this topic, you have surely assembled the definitive bibliography. Thank you very much for the offer—if you wouldn’t mind, please send it to amy@artofcounting.com

Thank you again for all of your insightful comments. I greatly appreciate your time and interest in this effort.

Best,

Amy

I do strongly appreciate your web paper on the ‘Nubian wig’.

I am nobody (cfr. Odysseus), just born 1939.

Was ‘it’ published and eventually what else.

I will have to check more of your written remarks.

Regards

PS: ‘to view history…’ as another example of the negative effect of writing.

PS: Top quality illustration which would have deserved printing !

PS: was M.Meilleur involved with some own writings ?

PS: who is ‘citizen’ Tassie ?

PS: regarding ‘ wig–black, blue, red, and white’, could it be some French flag ?

PS: I don’t know if statistical approach has any value, on the DOW or on the count of victims in Sadat’s Syria.

Hello Jacobus,

Apologies for the long delay–life has been very intrusive this past month.

Thank you for your comments! I am very glad that you enjoyed the article on the wigs and the other pages on the site. One of these days, I do hope to develop these remarks into an article for publication; thank you for your kind comments on my photos.

To answer your questions: Margery Meilleur was my grandmother. A sculptor and artist who was fascinated by history and how much the visual production of a culture could reveal. She supported me and my drive towards Egyptology from an early age. Without her influence and support, I would not have achieved the PhD.

G. Tassie is an Egyptologist who specializes in hair (his doctoral dissertation can be found here). His knowledge would certainly add significant nuances to this discussion of the lappet wig (of which, he is correct, there are several variations), but my primary focus here is to identify connections and larger patterns rather than investigating the specifics. The eventual goal with this project would be to identify such patterns and then provide that information to a researcher like Tassie who specializes in that material to aid their investigation. This is a collaborative process; it cannot be otherwise.

Thank you again and hope you keep enjoying the site!

Best,

Amy