Why was the looped sash worn at the king’s waist almost always painted red? What significance does this color hold and what message does it convey as a prominent regalia element? In the first post on the red looped sash, we discussed the use of sashes in general, outlined previous scholarship on the regalia element, and pointed out the occurrences of the looped sash in Ramesside royal tombs. That post noted that flowing sashes were connected to divine insignia and appear to have been related to the ankh, an important symbol of revivification. In this second installment of our examination of the looped sash, the focus is a general examination of the color red in ancient Egypt. Although it may seem a digression, it is important to this four-part discussion of the range of meanings inherent in the physical appearance of the looped sash that an investigation of its color be carried out.

Colors had great meaning and carried magical significance (see G. Pinch in Colour and Painting in Ancient Egypt). Red was an especially potent color–it was connected to the wild desert, primeval powers of creation, blood and violence, and certain aspects of the solar cycle. When depicted in color, the looped sash is almost invariably red, although I have found a few blue examples.

Ramses III in QV44 wearing a blue looped sash:

Red (desher) is a highly ambivalent color throughout Egyptian history. The color was associated with the deserts, and deshret (the ‘red lands’) stood in balance against kemet, the black land (i.e. the fertile Nile Valley). Through its relationship with the uncontrolled hinterlands, red was connected to virulent and chaotic powers, such as the raging of Seth and the monstrous snake Apophis, but red is also closely linked with the sun and represented the stalwart protection granted by the Eyes of Re who guarded the sun god on his journey.

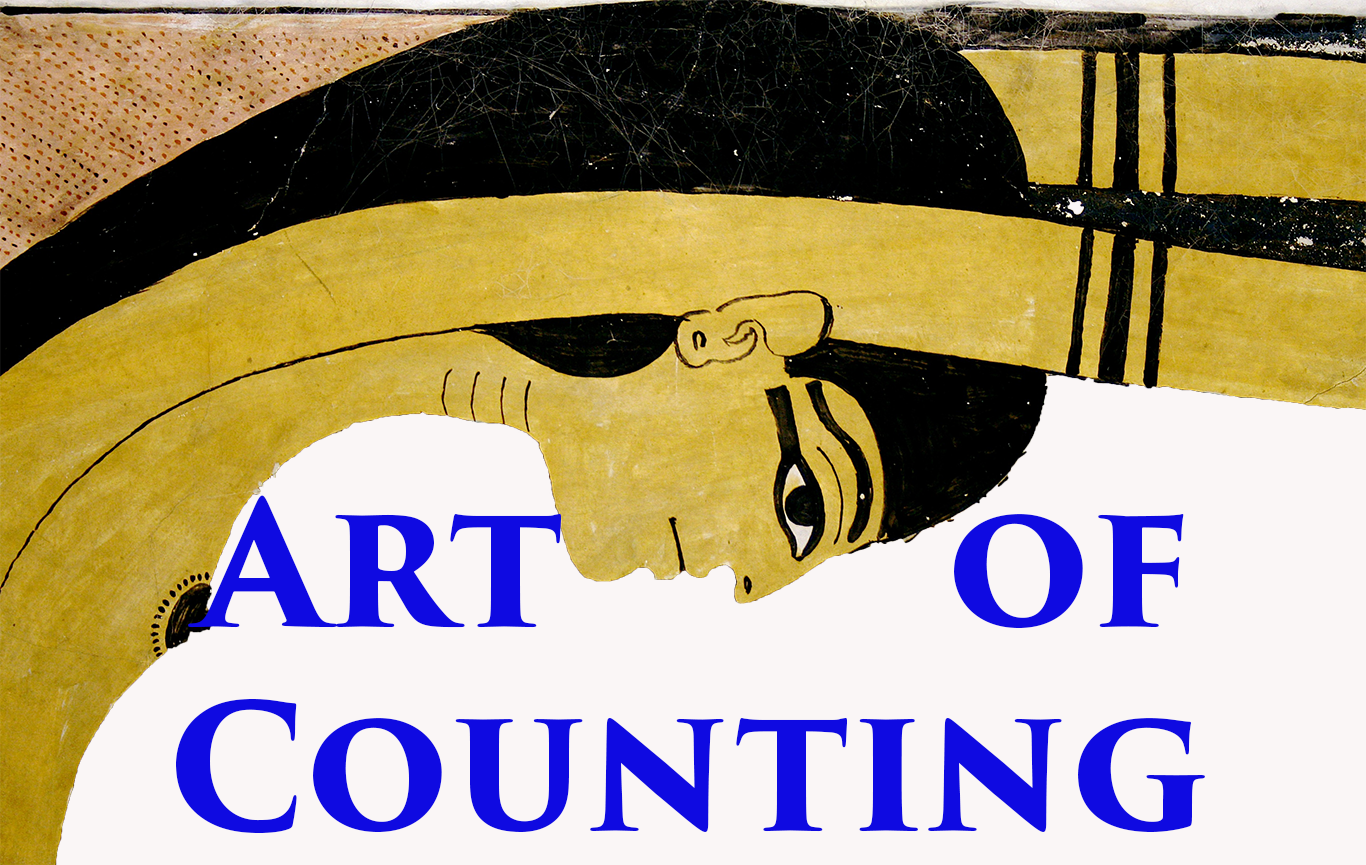

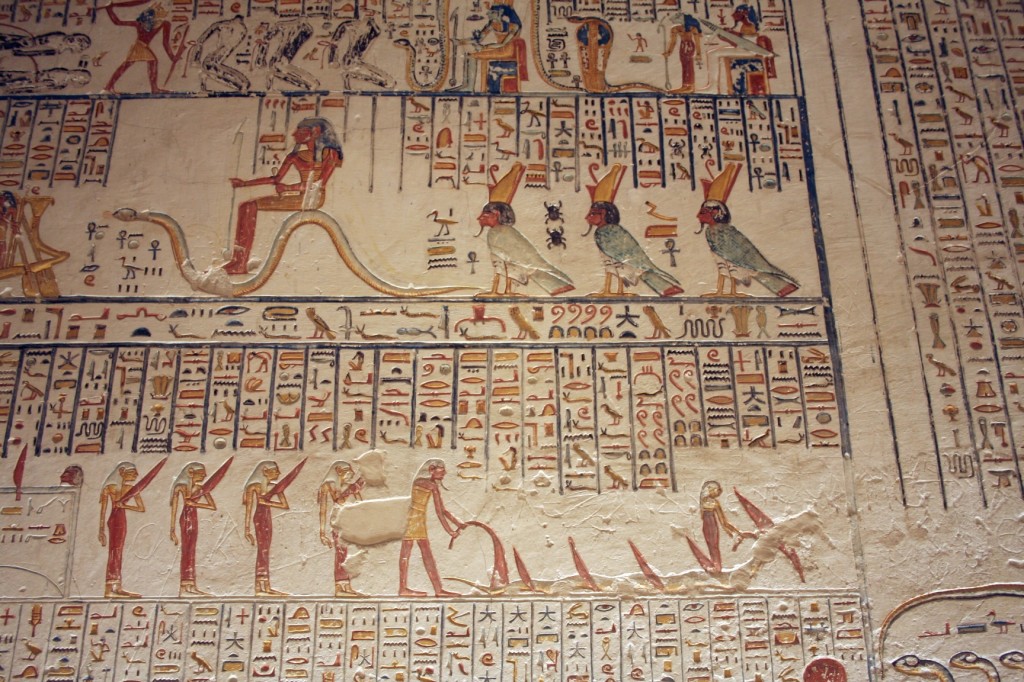

Apophis (Apep) bound in KV9:

The goddesses who could personify the Eye, such as Sakhmet and Hathor, are described in some magical texts as being clad in brilliant red linen. These potentially ‘angry’ goddesses are depicted in red clothing as well, such as Hathor in the tomb of Thutmosis IV.

Sakhmet at Medinet Habu:

Red was considered the morning and evening color of Re, representing that moment when he crosses the dangerous liminal zone of the horizon. When the looped sash appears in the costume of the living Amenhotep III, it, along with the apron embellished with disc-topped uraei, shebiu collar, armbands, and feather patterned aprons, was intended to identify the king with the sun. Many of these costume elements had been seen previously on pharaoh (from the time of Amenhotep II), but only in a particular context: where the king was portrayed in private tombs wearing these attributes, enshrined, and referred to as the sun god Re (W.R. Johnson, in Amenhotep III, p. 86)

Red and blood were intimately connected with the daily rebirth of the sun god. There are two major reasons for this association indicated textually. One of these is connected with Nut’s birth blood, which emerges with the disc and is called the “red flood” (in Coffin Text 407, for example).

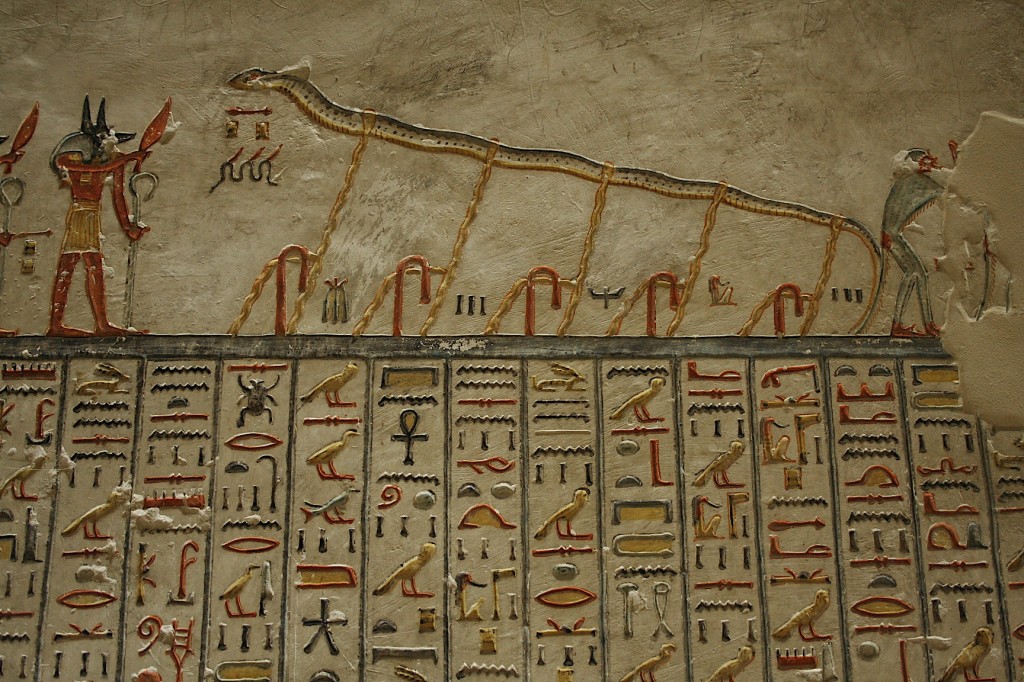

Ceiling in the burial chamber of KV9, showing the solar disc on it’s cyclical journey through Nut:

It is perhaps telling that in CT 714, the word ‘hahw,’ or ‘flood,’ is determined not only with a water sign but also a sky symbol. The text from the cenotaph of Seti I at Abydos indicates that, after his birth, the rejuvenated god “swims in his redness” (J.Allen, Genesis in Ancient Egypt, p.3).

Detail in KV9 of Re, shown as a red child, emerging from the netherworld at dawn:

The other, more aggressive, connection is made apparent in Pyramid Text 273-4, the “Cannibal” spell, which describes how the deceased king swallows his enemies in order to absorb their power (K.Goebs, Crowns in Egyptian Funerary Literature, p.207). The process is considered simultaneously destructive and creative, much like cooking ‘destroys’ the original ingredients, but the whole comes together to form something new. Herishef, the ‘ba who is in his redness,’ was associated with sunrise and presided over the Lake of Blood. This deity, who represented the united Re and Osiris and was associated with kingship and its transfer, commenced terrestrial kingship “as a result of Sakhmet’s bloodbath” (Goebs, 254) He was considered to be the actual embodiment of the aggressive dawn-form of the sun god. The ‘flood of blood’ apparent on the pre-dawn horizon “appears to represent the (chaotic pre-sunrise) basis from which the new creation emerges in the morning” (Goebs, 254).

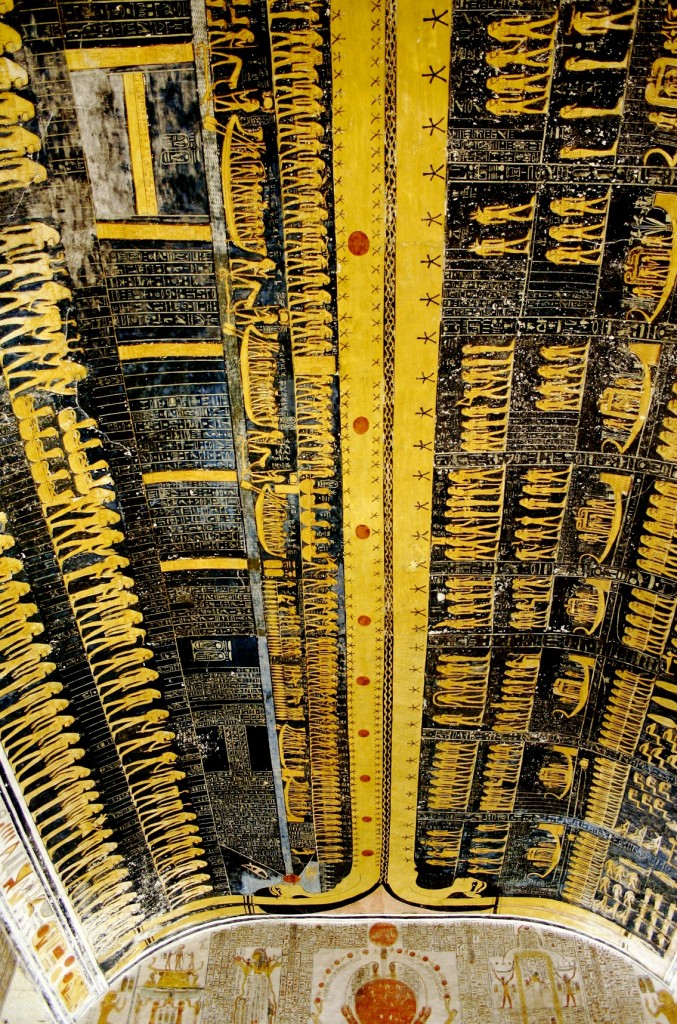

The sun god emerging in the burial chamber of KV9, surrounded by protective fire spewed from the uraei:

The protectively maternal and dangerously bloody aspects of red are explicitly linked in terms of the deshret crown in the text of CT 44 (Goebs, 201).

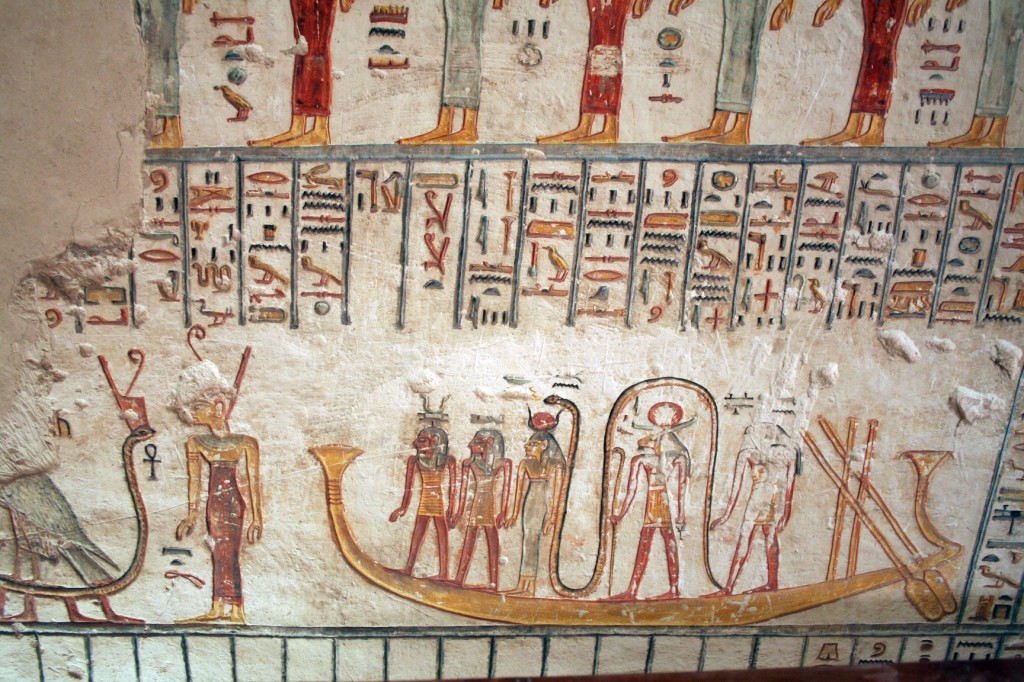

Detail of the solar bark in KV9; note the red-clothed goddess wearing the deshret crown standing before the bark:

This dualistic nature is further suggested by the various interpretations of the red of dawn. It has been noted, for example, that the ‘red flood’ could not only refer to Nut’s birth blood, but also to the ochre-colored beer that was poured out on the land to entice and appease the angry Eye (Goebs, 223).

According to the Seti I cenotaph text, it is seems clear that the sun was ‘born’ some time before actual sunrise. The duat is described as being not at the visible horizon, but rather “somewhat below the apparent intersection of sky and earth” (Allen, 6). The eleventh hour of the Amduat was called the ‘red-hour,’ and depictions of this portion of the solar cycle show four goddesses, wearing desert determinatives as crowns, who bear individual names like ‘Igniter.’ These aggressively protective females functioned to destroy the enemies of the cosmic process who were attempting to halt the solar bark and stop the sun god from rejuvenating creation at his rising. Since fire is their medium, these ‘reddening’ goddesses might be seen as manifestations of the Eye, the shining uraeus who burns the bodies of Egypt’s enemies with her flame.

Guardians of the sun god in KV9; note the four females holding large red knives, like those inserted in the body of Apophis:

In CT 648, the sun god at dawn is described as three in one—the self-created Re, Sakhmet overpowering his enemies, and the distant Horus who presides over the Ennead (Goebs, 303). If the rising sun can be simultaneously seen as Re and Sakhmet, the idea that the disc ‘drinks up’ the redness of dawn to emerge anew may also be related to the myths of the Distant Eye. The Eye is at first distant and angry, but once appeased, she brings ‘completeness’ to her father, Re. The ‘devouring flame’ that is the angry Eye “judges and gathers the gods” for the apparent slaughter of the stars that occurs at dawn (Goebs, 335). The sky progresses from night, which is full of ‘millions’ of stars, to the deep redness that spreads before dawn. This redness ‘eats up’ the stars, which lose their brilliance and seem to vanish under the progressive tide. Then the disc begins to emerge from the horizon, apparently ‘sucking’ the red flood into itself, until it separates from the horizon as the last trace of ‘blood’ disappears (Goebs 340).

The newly-reborn sun god emerging from the blood-red disc (detail in KV9 burial chamber):

The redness of dawn is also connected to Horus, the archetype of kingship. PT 404, for instance, includes a reference to the ‘Horus of (dawn)-redness,’ and the king himself is said to be “the redness that came forth from Nut” in PT 1460a (Goebs, 168). Horus is explicitly connected to red cloth in texts related to the ritual of the meret-chests at Edfu. The god is said to “…unite with the seshed-linen to overthrow your foe. You hold the red linen in its moment” (A. Egberts, In Quest of Meaning, 180).

Seti I offering red linen to Amun-Re at his Abydos temple:

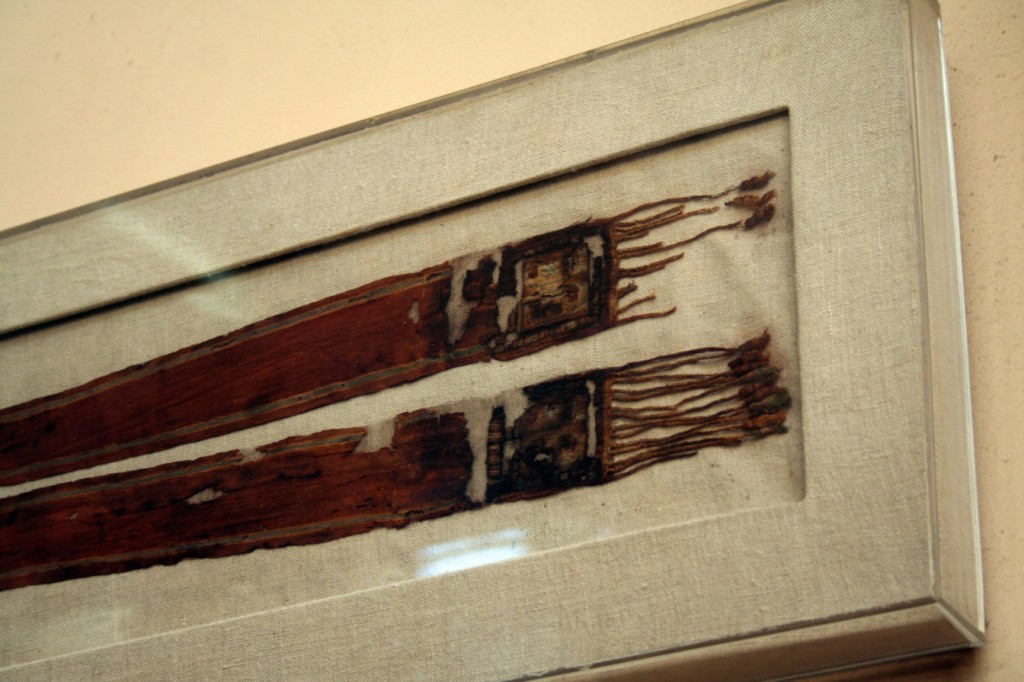

Actual royal examples of red sashes survive from the New Kingdom. There were three different types of sashes found in the tomb of Tutankhamun; undecorated simple, tapestry woven, and ‘Amarna-style’ (G. Vogelsang-Eastwood, Tutankhamun’s Wardrobe, 59). One of the ‘Amarna’ sashes is largely intact (JE 62647) and preserves a linen tapestry woven central panel with pairs of streamers extending from each side. Although they are woven with several colors, the decorated sashes are predominantly red.

Tutankhamun’s ‘Amarna’ sash as displayed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo:

Detail of Tutankhamun’s sash:

Also almost entirely red is the so-called ‘Rameses girdle.’ This incredibly well executed textile has been interpreted as a scarf, a jacket, or a belt, but has been recently reinterpreted (by G. Vogelsang-Eastwood) as an example of one of these long, looped sashes. It is delicately embroidered with ankh signs and originally displayed a finely executed line of text (now completely destroyed) that included the names and titles of Ramses III.

The looped red sash appears on the living king during the reign of Amenhotep III. Also during this period, a long red sash begins to be worn around the waist of royal women. This same type of crossed tie is well known from the iconography of goddesses in the New Kingdom, particularly Isis. It appears on Amenhotep III’s mother, Mutemwia, in TT 226 where he represents a form of the sun god and she stands in the position of a goddess. The sash was likely intended in this scene to tie her with the sky mother who ensures the sun’s journey. By the beginning of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the iconography of Isis “is indistinguishable from that of royal women” (L. Troy, Patterns of Queenship, 127).

Isis and Neith wearing the girdle tie in QV44:

As seen in the figure above, the shape of this tie worn by goddesses and queens is rendered quite distinct from the looped sash that appears on the king. This type of tie (which sometimes also appears on male deities) wraps twice around the body and is knotted at the waist in the front, with the ends dangling down the front. The king’s looped sash is wrapped an unknown number of times around the waist (it is generally concealed by a belt, layered on top of the wrapped tie) and knotted at the side, with one end loose and the other end tied into a loop. Both kinds of ties represent ritual knots that encircle the bodies of these beings, binding and protecting them while their bright coloration loudly announces their apotropaic significance. They may, in fact, be two different versions of the same fundamental attribute—a strip of cloth that ritually enfolds, conceals, and shields.

This red attribute, which encircles the body of goddesses and queens, may be directly related to the tyet amulet, the shape of which has been interpreted as a girdle tie. See the large blue and red tyet amulet behind Nefertum in the tomb of Horemheb (KV 57). This probable connection between the tyet amulet and the girdle tie would be consistent with the association of the protection of a mother goddess. The tyet amulet is usually made of carnelian or other red material (although they could also be blue) and is explicitly connected to the blood of Isis and the apotropaic role it plays for the deceased in the Afterlife. In addition, the amulet has been linked to menstrual blood and its place in reproduction. The element was specifically connected with the protective tie used by Isis to shield the fetal Horus when Seth tried to cause her to miscarry.

There was an apparently deep connection between the tyet and the ankh. Some early ivory fragments from Abydos show a tyet (rather than the ankh, as became usual) alternating with was signs, and both ankh–djed and tyet–djed combinations are preserved from the early Old Kingdom.

A frieze of djed and tyet signs at Dendera:

Even into the New Kingdom, the ankh and tyet remained strongly associated although clearly differentiated. They may even be viewed as two versions of the same thing, since the primary difference between them is the orientation of the ‘arms’—stiffened and held horizontally for the ankh as opposed to the softly rounded, flaccid arms of the tyet.

The above investigation suggested a range of possible meanings for the red looped sash. The associations of the red tie with the aggressive Eyes of Re and the morning and evening ordeals of the solar god, when he passed through the dangerous liminal zone, indicate that this attribute was related to a powerful form of apotropaic protection. Its similarity to the girdle ties worn by goddesses and queens, combined with the connection between both types of ties and the tyet and ankh, suggests that this ritual knot was not only protective but also contained a significant creative potential. It is possible that the particular meaning inherent in the sash may vary considerably depending upon the context and type of scene.

What do these aggressively apotropaic connotations reveal about the looped red sash? How does the connection between the guardians of the sun god and red ties fit in with the use of the looped sash as an item of royal costume? In the next post on the looped red sash, we will discuss the appearances of this element of royal regalia at Medinet Habu.

Dear Amy,

Do let me know if you would like to use any images of the ‘Rameses Girdle’

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/wml/humanworld/ancientworld/egyptian/collection/rameses_girdle.aspx

You have a really great collection of photographs! Thanks for sharing them.

Ashley Cooke

Curator of Egyptian & Near Eastern Antiquities, National Museums Liverpool.

Dear Ashley,

Thank you so much! I’d love to include an image in the post–I’ll link to the URL you provide above, if that is alright. It is great to have a good image for the ‘girdle’; it is such an amazing example of the ancient weavers’ skills!

I am very happy to share my photographs. Among the monuments I fully shot are the Seti and Ramses temples at Abydos, Medinet Habu, and several KV and QV tombs. I’ve started posting some in a gallery on the website and will be updating that regularly–please just let me know if there are any images you’d like to see posted or if you’d like copies of anything. Thank you again.

All the best,

Amy

What a fabulous article – so very interesting! Thank you for sharing it! From now on I shall definitely pay closer attention to the attire of the ancient Egyptians. Great job – keep up the good work. Best of luck. Holly McRae

Dear Holly,

Thank you so much! I’m glad my article has caught your interest. There are so many details in the king’s costumes–leopard heads and tiny skins at the top of the apron, jackal heads in the pointed ends of triangular kilts, and reshi-patterned (feathered) aprons, just to name a few–I find it endlessly fascinating. Very happy to have opened your eyes a bit more to the complexities of pharaonic costume. Enjoy the mysteries!

Best,

Amy

Dear Amy,

Your study is wonderful and I enjoyed reading it. Can’t wait for the next chapters. I am the webmaster of OsirisNet, a site devoted to the tombs and mastabas of Egypt, and I shall mention your publication in our next Newsletter. If we can help you with images, just ask.

Best regards

Thierry BENDERITTER

http://www.osirisnet.net

Tombs of Egypt

Dear Thierry,

Thank you very much for your kind words! I am extremely glad to hear that you are enjoying my exploration into the looped sash–should have part three ready by early next week. I am very familiar with your excellent site! OsirisNet is my first stop for information and images on tombs–your approach is quite thorough and the site is put together really well, making it a joy to navigate through the various monuments. Looking forward to your next release! I will definitely remember your kind offer for images, and please feel free to request reciprocation if there is anything I may have shot (such as QV 42, 43, 44, 55, KV 9, 11, Abydos temples, White Chapel, Medinet Habu, etc.) that you don’t currently have images for.

Thank you so much for mentioning the Art of Counting project in your next newsletter–most appreciated!

All the best,

Amy

Dear Amy,

We should be very glad to have your photographs of the QVs and KVs you mention. The shots illustrating your article are outstanding, and if the others are alike, they would greatly enhance our presentations.

As you know if you have subscribed to the Newsletter, we have released the tomb of Antefoqer-Senet (TT 60) just a few weeks ago : URL :

http://www.osirisnet.net/tombes/nobles/antefoqer/e_antefoqer_01.htm

While I was preparing it, Jon Hirst was working on TT 38, Djeserkareseneb, which will be launched…today. Here is the URL :

http://www.osirisnet.net/tombes/nobles/djeserkareseneb38/e_djeserkareseneb_01.htm

We hope you will like it.

Could you give me your private mail ? Mine is clb83130@yahoo.fr . It would be easier to communicate.

Yours sincerely

Thierry

These pictures are quite beautiful and remind me of my visit to this tomb during a break in my US Navy deployment for Operation Desert Shield in October 1990. I am in the process of writing an essay for my literary blog detailing what seeing this ceiling first hand did to me spiritually. As such, I would love your permission to use the photo that has as its description, “Ceiling in the burial chamber of KV9, showing the solar disc on it’s cyclical journey through Nut:”

If you decide to grant me the permission, please share with me in a private message how you would like to acknowledge and credit you for use of this photo. Also, I would love to link to this post in the final draft of my essay.

Thank you in advance!

Eduardo

Thank you, Eduardo. I will reply directly to you soon!

Best,

Amy

Where abouts is the red sash of TUTANKHAMUN? Is it in the Cairo museum? what book is it published in? would like more information? looks interesting

It is in the Cairo Museum. In 2006, it was hanging high on the wall to the left above the cases of the king’s sandals, which is where I photographed it (albeit badly due to the lighting). It has been published several times, mostly in passing. G. Vogelsang-Eastwood talks about all the king’s sashes in Tutankhamun’s Wardrobe, pages 58-62.

Thank you for your comment!

Best,

Amy

Dear Amy,

I hope you still respond to this article. It is a very interesting article that gives a good overview of the red looped sash but my question for you is this: Do you think that sashes which are represented on the walls have more resemblance to the girdle of Ramesses II or the sash of Tutankhamun?

Do you have any more pictures of that particular sash and if you do, is it possible for me to use them in a paper I am writing for my MA course about the sash of Tutankamun. I found it hard to find good color pictures of the sash. Secondly what are your other thoughts on the sash, because I think that you can’t compare this sash to representations of the Ramesside since their ideas are probably very different than those of the kings in the 18th dynasty, more evolved so to say. And third: Is the loop such a big factor when someone is wearing the sash, is the red sash the most dominant feature or is only a combination represented?

To finish up. Thanks for this article, it has given me a lot of new insights. Good luck with any further work.

Kinds regards,

Davide Monteiro Snepvangers

MA-student Egyptian language and culture, Leiden University

Dear Davide,

Very happy to hear you found the article to be useful! I agree that the looped sash is more in line with the Ramesside girdle of Ramses II rather than the red sashes of Tutankhamun, but included it to discuss the evolution–I do think they are connected conceptually. Tut’s red sash was very hard to shoot, but I am glad to share with you all the photos I was able to get of it. The form is clearly different and, when shown in relief, displays the two long tails on either side of the body. I look forward to seeing your research on it!

As far as the later examples, it does seem clear that the loop is an integral part of the regalia. There are numerous examples (especially later, such as on Herihor at the Khonsu temple, but also on some monuments of Ramses II) where only the loop is rendered in relief and the trailing part of the sash is painted. When the loop initially appears in the latest phase of Amenhotep III’s costume, it is also only the loop that is depicted. This article sums up the findings from my PhD dissertation on this emblem at Medinet Habu–let me know if you would like a copy and I will send that along as well.

All the best,

Amy

Dear Amy,

I would love to have read your article since I think it will help me a lot! Thanks again for you help and fast response.

I also think that the ‘Amarna’ sash is connected to the later sashes, but did you ever come across one image where the sash is decorated with cartouches? I haven’t found them yet.

Kind regards,

Davide Monteiro Snepvangers

MA-student Egyptian language and culture, Leiden University

Dear Davide,

My pleasure! I will send you the download link.

No, I haven’t seen a depiction of a sash with cartouches yet; the ‘Ramesside girdle’ has them though. The only variations I have seen on the sash are: ways the tail is rendered–sometimes through the loop, sometimes not–the size of the loop, and (very rarely) the sash is colored blue instead of red. Now, of course, it is possible that some examples had cartouches painted on them originally and they are just worn away, but at least among the well preserved mortuary examples, none of them appear to have such embellishment. I do wonder if these red sashes are in any way related to the ones worn around the neck of Hatshpsut’s Osirid figures at Deir el Bahri (also seen on the White Chapel and elsewhere), which end in ankhs, but that may be too far afield.

Best,

Amy

Lovely article and pix! Thank you so much, and I shall now follow you!”

Thank you very much! Glad you enjoyed it.

Dear Amy,

Fantastic images (sorry to be late to the party). Ashley Cooke suggested I drop you a line. Would we be able to discuss use of your images in a project that I’m developing here at the University of Liverpool?

All best,

Glenn