Is the red looped sash worn at the king’s waist simply an elaborate tie used to hold up the royal kilt, or does it have an inherent significance? If it did carry meaning, what made it appropriate for particular contexts but not for others? The Art of Counting Team believes that it does have meaning, and has the data to back it up. This is the first of four articles that will explore the red looped sash.

Due to the length and complexity of this discussion, this information will presented as multiple posts. We will begin with a brief examination of the general use of sashes in ancient Egypt, the significance suggested by some previous research on the looped sash, and the appearances of this regalia element in royal Ramesside tombs. The second post will focus on the significance of the color red in Ancient Egypt, the third installment will examine the appearances of the looped sash at Medinet Habu, and the final article will explore the meaning of the looped sash as royal regalia based on the data.

This prominent attribute of royal regalia first caught my attention several years ago in the temple of Seti I at Abydos where it occurs at least 15 times, often as part of some especially elaborate royal costumes.

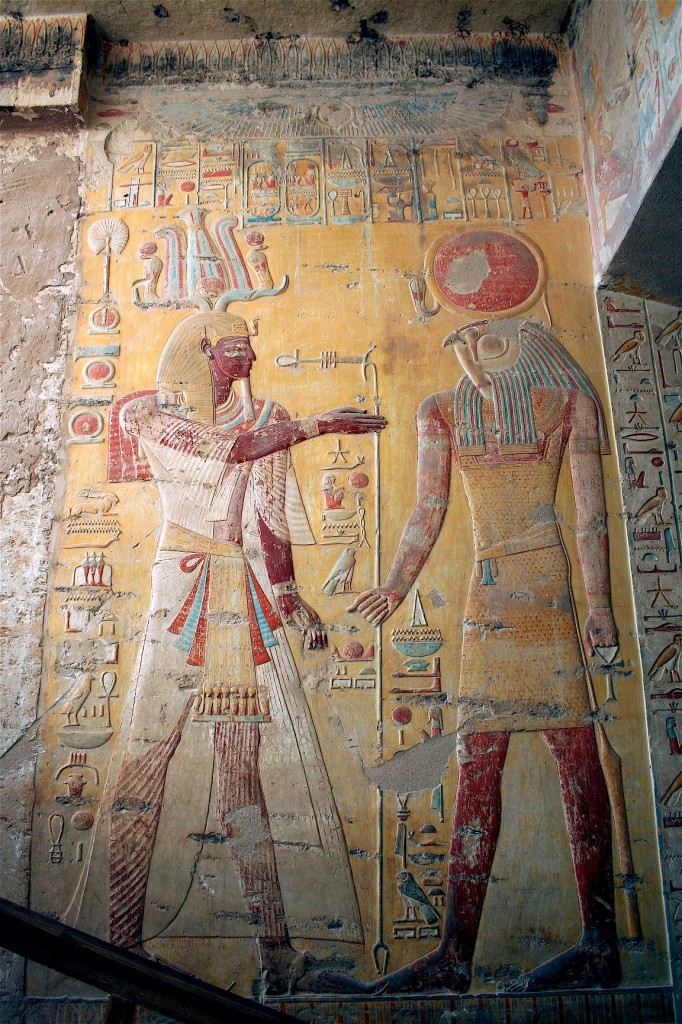

Seti I wearing a red fabric shirt, armbands, double shebiu collar, multiple apron, and looped sash:

Seti I wearing a looped sash while grasping a rekhyt bird:

Seti I wearing the looped sash while receiving the breath of life:

Detail of looped sash from an offering scene rendered only in paint:

This element has been briefly discussed by scholars, but there has not been an in depth examination of its usage and significance. Largely for this reason, this looped sash was one of the regalia attributes I researched in my dissertation project focusing on Medinet Habu. The analysis of usage patterns for this attribute revealed some strong tendencies for the sash to be worn in particular situations. The data clearly showed that there is a close connection between the sash and scenes of violent action, those that legitimize the king’s rule, and to those moments where the pharaoh is passing through a transitional, or liminal, zone.

Background—use of sashes and previous work on the looped sash

Plain sashes were used from as early as the Old Kingdom by men of all social classes to hold their kilt in place; however, the very large, red loop and long sash seen in the costume of the king is clearly not intended simply to secure his kilt. Like the red streamers that hold some crowns in place (see second image of Seti above), a sash needn’t have been so prominent to serve this basic function.

Binding and the tying of knots were used in acts of creation and protection (R.Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice, 144). Knots were not only amuletic, but they could be viewed as a symbol of the hidden force of germination. Strips of cloth were clearly important in cult from early in Egypt’s history, as the cloth-wrapped netcher sign (‘god’) attests.

Netcher-sign from the White Chapel:

It has been noted that djed pillars, divine emblems, temple facades, and New Kingdom kiosks often display streamers, and these are considered to be similar in conception to “the fluttering streamers attached to royal headgear…as well as the innumerable long pendant strips that form part of the dress of deities (and) royalty.” (E. Hornung, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt, p.37).

Relief at Luxor temple showing facade with four triple-streamer flags:

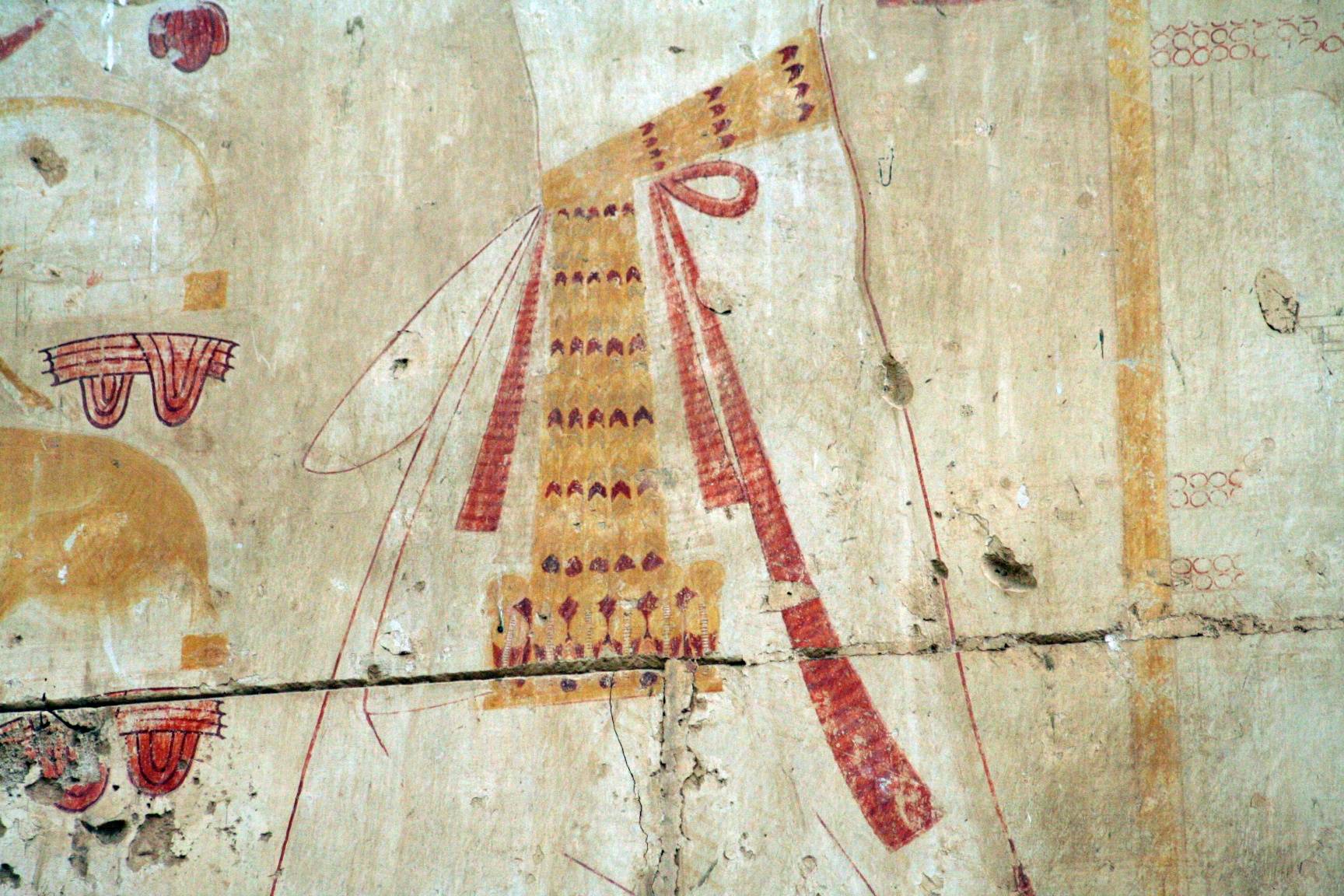

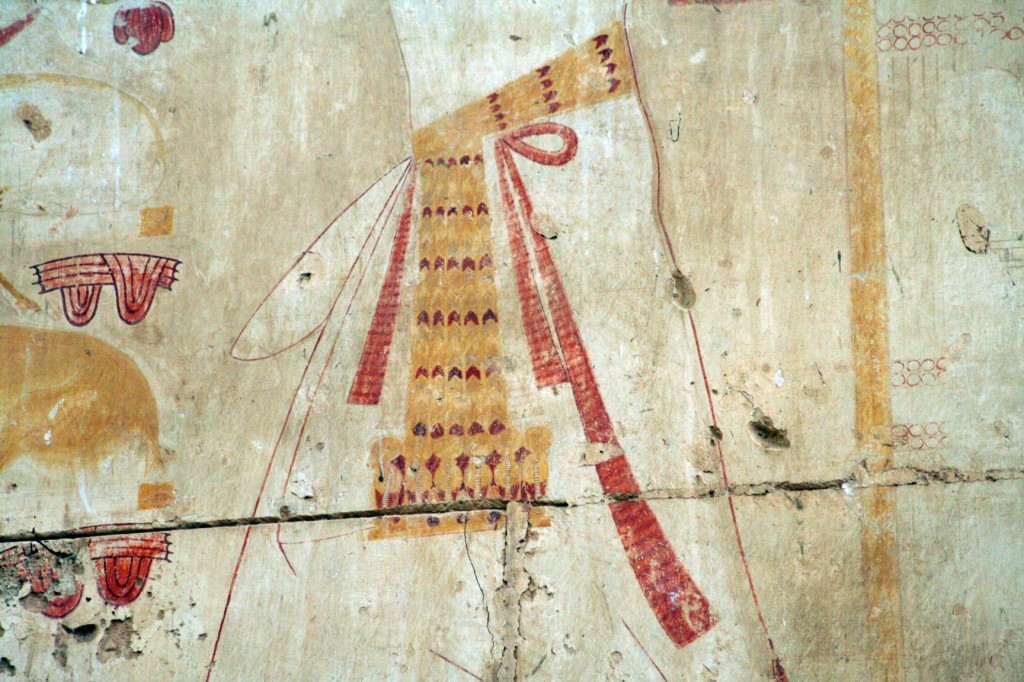

Divine emblems at Medinet Habu with red streamers:

Detail of djed pillar in Valley of the Queens (QV) tomb 44 with pendant sashes:

It has been suggested (by W. Westendorf) that these long pendant strips, which appear on goddesses early in the New Kingdom, may be symbolically related to the ankh. Particular forms of penis sheaths have likewise indicated a connection between these cloth belts worn by workmen and the ankh (see J. Baines in SAK 3). However, the large looped sash appearing at the king’s waist has not been extensively discussed in these studies.

However, the looped sash is mentioned in the Egyptological literature on numerous occasions (such as by W.R. Johnson), mostly in terms of its appearance in the intensely solar iconography that appears on Amenhotep III after his jubilee. The major hallmarks of this solar costume besides the looped sash are the panther head (or tiny skin) at the top of the apron, the shebiu, and the armbands.

Amenhotep III wearing a ‘Phase III’ costume on the facade of the Colonade Hall at Luxor Temple (from W.R. Johnson in L. Berman, ed.):

Detail of panther head at top of multiple apron and looped sash on a standard-bearer statue:

Elements of this elaborate solar costume of Amenhotep III appears in the scenes of the king on the great bark of Amun depicted on the Third Pylon at Karnak, on statuary, such as the well-known purple quartzite depiction of the king found in the Luxor cachette, and also in some private tombs, such as in the tomb of Anen (TT 120) where he is enthroned in a kiosk.

Detail of the purple quartzite statue showing looped sash and a feathered back kilt:

Amenhotep III and Tiye in TT 120. Only the trailing sash is preserved, visible just behind the king’s calf:

This costume continued to be used after Amenhotep III to identify the king as sun god, and the looped sash appears in a number of the New Kingdom royal tombs, beginning in the tomb of Seti I. It is often part of the elaborate costume worn by the king in the Litany of Re scenes that appear at the top of Ramesside royal tombs.

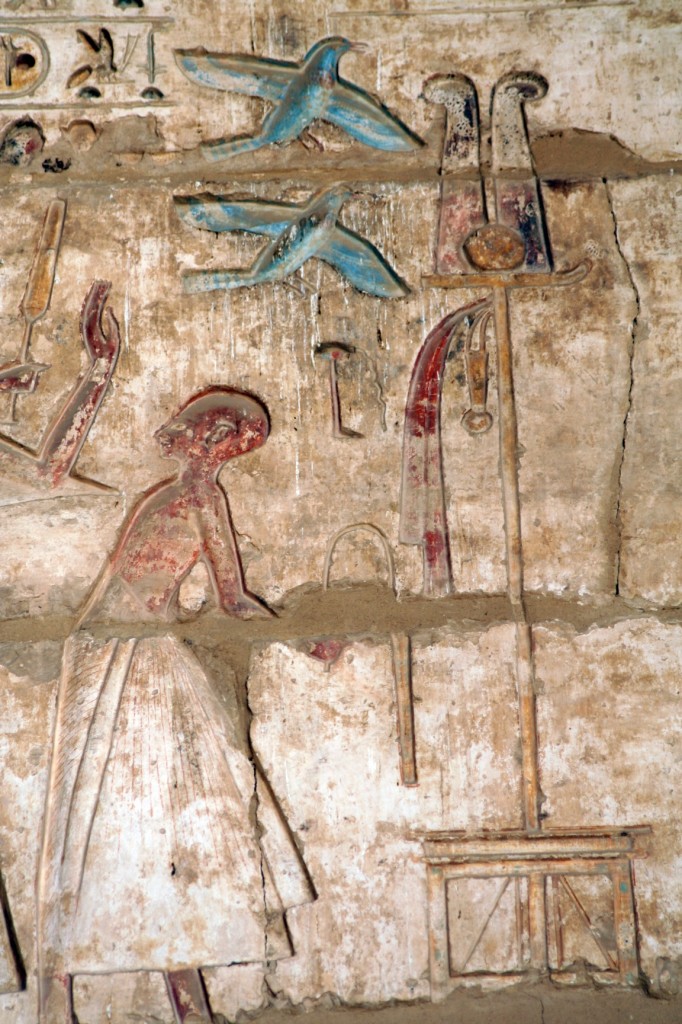

Litany scene in Valley of the Kings (KV) tomb 8 (Merenptah):

Litany scene in KV 47 (Siptah):

Litany scenes in KV 15 (Seti II):

Litany scene in KV11 (Ramses III):

Detail of kilt in KV11 Litany scene:

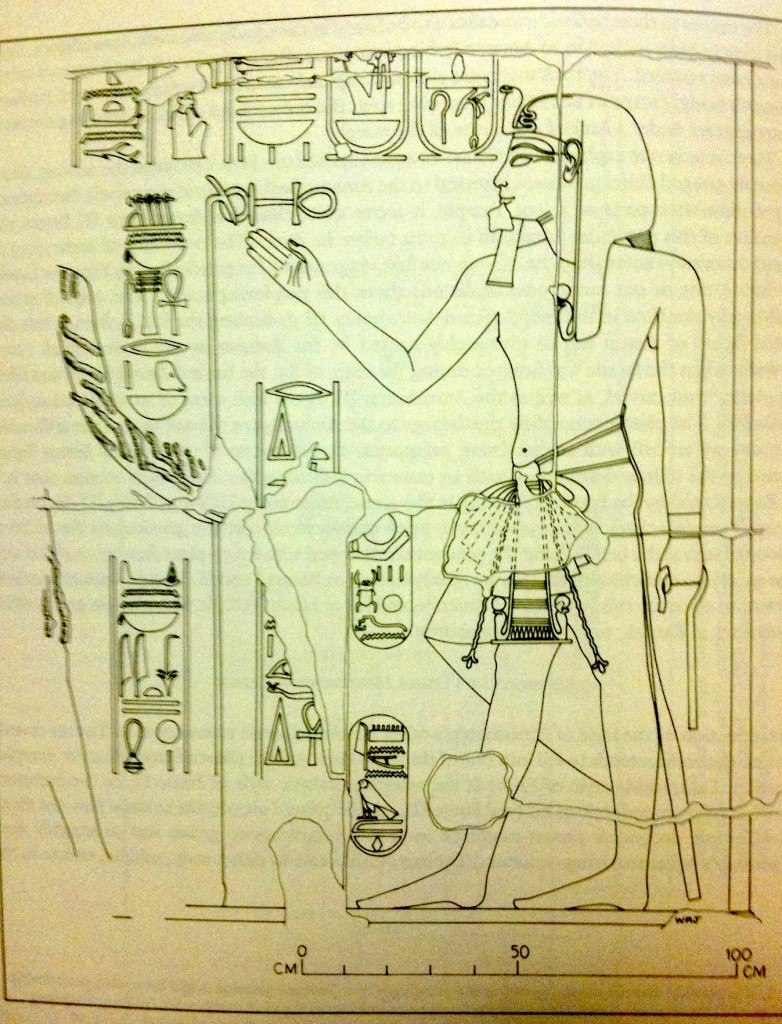

The looped red sash was undoubtedly considered to be a very essential piece of regalia in certain contexts. See, for instance, the below figure from the tomb of Seti II (KV 15).

Sketch of king in KV15:

This image of the king wearing a lappet wig, and its mirror on the opposite wall, were only basically indicated in red ink. Although the depiction of pharaoh was never executed in any manner beyond this outline, the looped sash is clearly visible and very prominent. Several similar examples can be found in a side chamber in the tomb of Seti I (KV 17), where preliminary sketches on the pillars clearly show the looped sash among the king’s regalia. The red looped sash is seen on many royal images in the Ramesside tombs, often in the outer corridor and also deeper within the tombs, and it seems to increase in frequency as time passes. For example, although in the tomb of Ramses III (KV 11) the sash is worn in the Litany scene seen above, only two of the five offering scenes within the corridor, and at just once in the pillared hall, almost all of the images of the king in the pillared hall and burial chamber of Ramses VI (KV 9) wear the looped sash.

Offering scene in KV11:

Pillared hall in KV9 (Ramses V/VI):

Burial chamber of KV9:

In the tombs of the sons of Ramses III in the Valley of the Queens, Ramses wears the looped sash in all of his depictions, at least where it can be determined. In these tombs, pharaoh is shown preceding his sons and interceding for them before the gods and gatekeepers of the Netherworld.

Ramses III before his son in QV44 (Khaemwaset):

Ramses III before his son in QV43 (Sethherkhepshef):

Although the looped sash is an element restricted exclusively to the king’s use, in many of the scenes his sons wear one of their floral sashes looped at the waist in imitation of the king’s red loop.

Detail of king’s kilt in QV44:

Detail of prince’s costume in QV44:

Why was the looped sash so prevalent in Ramesside royal tombs, and why did its usage increase in frequency over time? What meaning did this exclusively kingly attribute hold that made it so appropriate for a funerary context, especially since in other contexts (such as on temple walls) it was often worn in scenes of battle, slaughter, and violent action? What about it made the looped sash desirable for the princes to imitate in their costume?

In the next installment of this examination of the looped sash, we will explore the significance of the color red in an effort to gain a deeper understanding of the meaning inherent in this enigmatic element of royal regalia.

thanks for fotos

You are most welcome!

Very interesting. Mormons are much in the news of late, and there are many comments about our temple rites; mostly negative. You may be aware that our temple regalia includes the sash with the large bow; now I understand more of its significance. Thank you so much.

On a related subject, there is so much more that is familiar in these ancient scenes. The apron, for example, and more to the point, many of the stances and gestures, which are sacred representations of various aspect of Kingship and Godhood. Hugh Nibley was written some on the parallels with the Mormon temple rituals, although his work is really intended to be understood only by initiates.

See a short summary here: http://chapmanresearch.org/PDF/An%20Egyptian%20Endowment.pdf

The drama is an ancient one, eternal in nature, and when we look at the Egyptian experience, even when shown just a few “snap shots,” it is fairly clear what parts of the drama are in play. The level of appreciation for an endowed member of the LDS church goes well beyond that of the uninitiated. For example, if you see two pictures, one of a football game, and one showing the Queen and her court, you should know that its the HS homecoming game; and you know something about the associated ritual. A few generations back, every school child would have been familiar with the May Pole, (complete with streamers?) and the selection of the King and Queen of the May. Its the same with the temple endowment. You have to know the drama to understand the snap shots.

I would think that an Egyptologist would have some difficulty understanding what’s going on without having participated in certain aspects of the ritual drama.

Thank you again for the “most excellent” post.

Thank you for your comments, Donald–I am glad you found this information to be of interest.

The Art of Counting project is focused solely on quantifiable data–we only deal with what we can back up with a wide array of supporting information. No disrespect intended, but one must be very careful when attempting to overlay modern conceptions onto ancient imagery. Similarities of appearance do NOT necessarily imply similarities of conception. The interpretations of ancient Egyptian temple ritual suggested in the reference you provided were highly problematic.

If you are interested in actual scholarly discussions of the Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyrus, please see Robert Ritner’s work on the topic. You can find discussion of his new book, providing a complete translation here, and a pdf of his JNES article on a section of the ‘Book of Breathing’ here.

Thanks for the information and nice pictures.