In the wake of the Jasmine Revolution in Egypt, as the infrastructure shifts and uncertainty persists, Egyptians continue to aggressively protect their heritage. Egyptology News reported last Friday about the thwarted looting at Aswan of a 6 meter tall, 160 ton red granite colossus of Ramses II. Quick action by the guards at the site and the local archaeologists resulted in the red-handed capture of the looters. These brave people and their compatriots continue to guard the global treasures in their care with inspiring tenacity, but there is no arguing that unknown numbers of antiquities have been damaged, lost and destroyed during these last weeks.

Looting continues to be an issue in many areas–recent reports include a large-scale attack on magazines south of Giza, where 60 thieves gagged and bound the guards and gained access to the storage areas. Inventory is being carried out to determine the extent of the damage. There was also an attempted looting of a site near Edfu and the Czech archaeological mission has confirmed massive damage at their Abusir excavations. An unconfirmed list of objects missing from the Cairo Museum includes several artifacts not previously mentioned, such as one of Tutankhamun’s trumpets and the contents of an entire display case (save one lone turquoise hippo).

Most distressing, yesterday Zahi Hawass announced the widespread looting of many sites over the last several weeks, including at Abydos where illicit digging reaches to 5 meters in parts of the site. As an Egyptologist, it was very difficult to read through the list outlining the extent of the damage. Dr. Hawass subsequently announced his resignation as Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs in protest (or did he?):

“The police cannot do enough, or anything to protect Egypt’s antiquities and treasures, and I can’t stand by while that happens,” he said. “It is a protest really, that not enough can be done now to protect these sites and treasures.”

The future of Egyptian Antiquities management and protection is currently uncertain at best.

Such incidents of looting obviously have the potential to inflict a massive loss or extensive damage in a single event, and the news about these ongoing events sicken the soul, but many Egyptian monuments have faced an onslaught of slow degradation at the hands of tourists for decades. “Being nibbled to death by baby ducks” is a colloquial phrase that comes to mind.

My last journey to Egypt in 2006, I was horrified by the rampant and reckless destruction wrought by visitors to the sites and museums. During my 10 days photographing in the Cairo Museum, I had to repeatedly remove gangs of children from the back of a Ramesside sphinx, shoo a man who was trying quite hard to pull the ram-headed stopper off an offering statue, holler at a couple who were casually picking pieces off of the Dashur boats and flicking them at each other, and chase a teenager who was carving his initials into a royal statue. And I was only in the museum a few hours per day. To be fair, I have seen similar incidents in major European and American museums too (a banana peel on the Rosetta Stone?!?!)–if it is possible to touch something, some people just will, regardless of whether or not one actually should–but these things happened in Cairo with astonishing frequency and most of the guards were utterly indifferent.

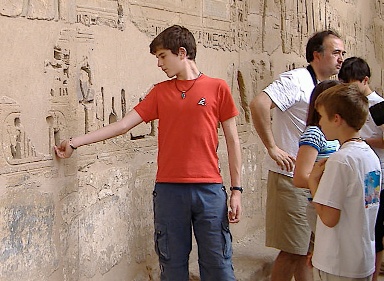

It was at least as bad, if not worse, in the monuments. My wonderful SCA inspector, Salah, who was with me the entire time I was photographing, spent a large chunk of the time yelling at people and telling them to stop picking at the walls. Most tourists would completely ignore us until we were right up on them, and even then they tended to just shrug and walk off to pick at another wall. It was extremely frustrating, as the situation has long been for anyone trying to study these monuments and who treats every square centimeter as a precious gift from antiquity. To document these activities, we began to photograph these tourists behaving badly and I have been publishing those images online in an effort to highlight what NOT to do when visiting a global treasure.

These monuments, particularly the temples at Thebes, face a daily onslaught of hands rubbing at their surfaces. It is no wonder that in many temples the relief is in such abysmal condition on the lower 6 feet of the wall–that is where most of the touching has been done. And always has been. Surely the Greek travelers who left their graffiti throughout Egypt did plenty of wall fondling along the way, and it is likely that those who wandered these ruins in the millennia between the time of the pharaohs and our own touched their share of relief.

Many of the monuments had sections used as dwellings or churches in this ensuing period, with centuries of habitation or constant use taking an incredible toll.

However, there are several reasons why a touch that might have caused minimal harm in centuries past may be instead the last straw for a crumbling relief that disintegrates after the fondler walks away. One major difference now is the density of people visiting these monuments. The number of people has increased exponentially over the last several decades, with some major monuments receiving thousands of visitors each day. Even the most respectful tourist causes damage through the moisture exhaled in our breath–a particular problem in the tombs. Simply by being visited by these kinds of numbers, some monuments can be irreparably damaged.

Unfortunately, not only the tourists were guilty of manhandling the monuments. Some of the guards used ancient statuary as seating.

Others rock Roman pillars in the ruins of Luxor Temple in a bid to impress girls passing on the corniche.

There are many truly stellar Egyptian guides, those that provide their groups with detailed, accurate information delivered with an ingrained respect for the monuments, but they are not all so good at their jobs. Some of the guides, the very ones who bear the heavy responsibility of educating Egypt’s visitors, tap on the walls of Nubian temples with a cane to point out details of the relief or actually encourage their guests to fondle the walls. This type pf practice produces masses of people who then wander about touching walls at will, observed by other tourists who note that no one fusses so they assume it must be a fine thing to do.

It spreads like a virus.

Many people, like the man above, touch the walls with intent. He wasn’t just touching the painted relief, he was stroking it, quite purposefully, and fully experiencing the texture of the ancient mineral pigments under his fingertips. This desire that is the fundamental driver of most of the touching is not hard to understand–in the face of such an undeniable statement of the passage of time there is a deep impulse to connect with it physically. That tangible, tactile moment is likely for many people a treasured lifetime memory, a concrete connection with something much larger than themselves. At least the painted relief he was rubbing on has been photographed; even if he rubbed all the paint off, we would happily still have a record of it. This is unfortunately not usually the case.

Some people handle the monuments as though they are their own personal Disney World. They happily lean on a section of painted relief as they walk by and treat statue niches and ancient statuary like benches.

Some are even actively destructive, picking bits of relief off the wall as casually as if they were flicking some lint off the carpet.

Another of the big problems is that it is easier than ever to knock relief from the walls by the slightest touch. Since the construction of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960’s, the water table has elevated and the soil is no longer flushed by the annual floods. This has resulted in perpetually wet soil that is super saturated with salt. Porous stone sucks this saline water up like a sponge and then, as the water evaporates, the salt crystallizes just under the surface and expands until it pops the relief off.

What remains when the relief falls off is bare rock.

At the Seti I memorial temple in Gurna, I photographed a colossal statue base at the entrance decorated with bound prisoners that was suffering badly from salt crystallization. The images below clearly show how the relief is separated from the block.

These bound prisoners have since fallen and broken into many pieces, like those visible along the front of the base in the above image. When relief is in this condition, even a breath is enough to dislodge these treasured pieces of ancient imagery and scatter them in pieces on the ground. Even with the successes of many active dewatering, desalinization, and stabilization projects that have been initiated over the last several years, salt crystals already in the stone will continue to wreck havoc for years to come.

At this moment, when there is such upheaval and such fundamental concern for the protection of sites from looters, we must obviously focus our attention there. Once the country stabilizes and tourists begin to return, a concerted effort to educate Egypt’s visitors could significantly reduce these incidents of relief fondling and help preserve these treasures. For now, however, as the director of the Metropolitan Museum stated:

“The world cannot sit by and permit unchecked anarchy to jeopardize the cultural heritage of one of the world’s oldest, greatest and most inspiring civilizations. We echo the voices of all concerned citizens of the globe in imploring Egypt’s new government authorities, in building the nation’s future, to protect its precious past. Action needs to be taken immediately.”

The illicit digging and mass thievery has to be brought under control, as quickly as possible and by whatever means is necessary. As reported on CultureGrrl’s blog, Sarah Parcak points out that there are numerous international organizations that have offered to help guard the monuments and sites, but their hands are tied without permission.

The unknown amount of damage currently being done to sites all over Egypt is the nightmare of every Egyptologist come to life. The ever astute Eloquent Peasant has summed up these fears succinctly:

And that is one of the things that I fear for most now, for that which we may never even know we have lost: the archaeology and objects that have never been properly recorded before being destroyed forever. Illicit digging at at least eight different sites across the country may prove in the end to be the worst casualty.

The loss of what wasn’t properly recorded is a true and total loss. As the Art of Counting is poised on the cusp of releasing the beta version of the new Master Egyptian Database to our project collaborators to begin populating it with material, all we can do is weep that this type of effort wasn’t in place many years ago and focus our attention on recording as much as we can as quickly as possible.

March 7th Update: On his blog, Dr. Hawass discusses his resignation (Andie at Egyptology News provides a summary of the situation). Dr. Hawass also announced the extensive looting of Buto, a very important site in the delta region, which took place on Friday.