Sincere thanks to Tom Hardwick for his astute comments and suggestions in the crafting of this two-part post

In a previous post, I outlined the basic history and significance of sandals and discussed the apparent usage patterns of royal sandals at Medinet Habu, based on the results of a tetrachoric correlation analysis performed on a selected dataset. Now that the entire temple has been entered into the database, I wondered how consistent these patterns would remain when the dataset was expanded to include all the scenes from Medinet Habu. In this expanded dataset, the king wears sandals in 129 (16.8%) of the 765 scenes, compared to 27% of the exterior and courtyard wall scenes selected for the dissertation, but many of the patterns remain.

Where the datasets are consistent

Of the 21 scenes within the temple where the king is depicted seated, he wears sandals in 15 of them (71.4%). Only three scenes clearly show that he is not wearing footwear (the rest being too damaged to discern), and these three all show him being purified with streams of water or being worshiped as a deity.

In all scenes where it can be determined, the king wears sandals every time he is presented with spoil; these often show him standing in a balustrade. Sandals are also worn in 20 of the 23 scenes (87%) where the king presents battle spoil to the gods.

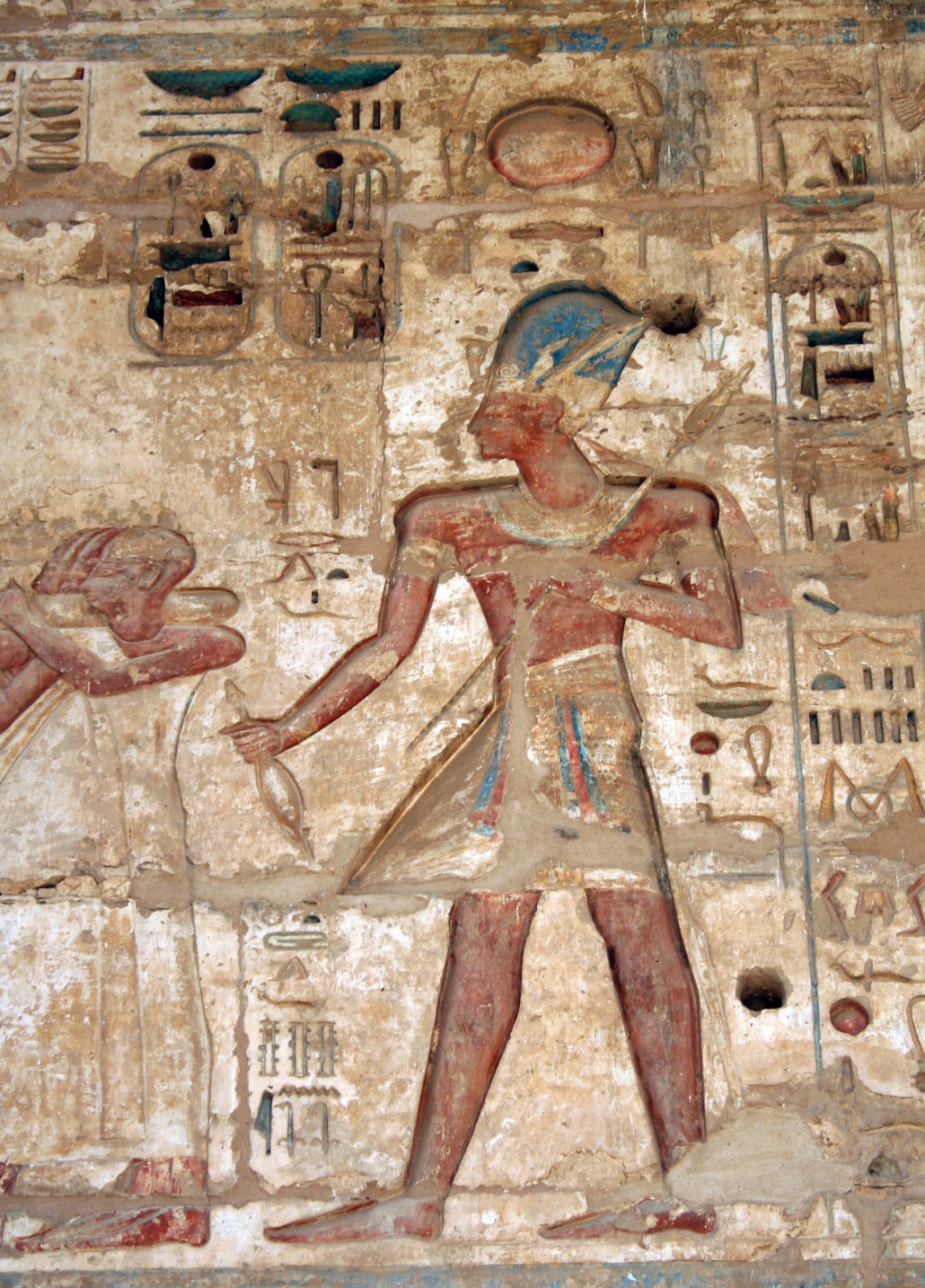

Ramses standing at a balustrade being presented with prisoners and spoil:

The khepresh crown is the most commonly used headgear with the sandals (47 times—36.4%), followed closely by the lappet wig (35 times—27.1%). The other crowns are more rare, although almost all —except the sehemty—are worn with the sandals at least a few times. It is interesting that the only instances of sandals being worn with the deshret (red) crown or hedjet (white) crown are three scenes found in the treasury where Ramses offers bags of gold and ingots and a fourth scene that preserves the only instance of a deshret crown combined with shwty feathers in the entire temple.

Red crown and sandals worn together in the treasury:

White crown and sandals worn together in the treasury:

Considering its relative rarity among the 765 scenes (with only 77 examples vs. the 441 examples of the flanking apron), a strong connection remains between the sandals and the multiple apron. They are worn together 50 times (64.9% of the instances of the multiple apron).

Multiple apron worn with sandals:

Sunshades and sandals are almost always used together (23 of the 28 times sunshades appear)—there are only five scenes where sunshades are held behind the king where it is not clear if he wears sandals, and these are all of pharaoh in his chariot where his feet are not visible.

Ramses processing in his chariot:

Where the datasets differ

First, let me say that the datasets show far more consistency than they do differences. With the expansion of the dataset to include all scenes at Medinet Habu (not just from walls, but on pillars and columns as well), the proportion of scenes where the king wears sandals in conjunction with depicted deities increased. There are 58 scenes in the expanded dataset (44.9%) that include humans but no deities, 53 (40.3%) that include deities but no humans, and 17 (13.1%) that include both (the majority of these being smiting scenes or those of the king presenting bound foes and spoil).

The expansion to the full 765 scenes also shifted the pattern related to smiting scenes, although there are clear divisions in those that use sandals and those that do not. Sandals are worn in nine smiting scenes (out of 27 such scenes—33.3%), specifically those found on both sides of the walls of the Window of Appearance and the smiting scenes found on the East High Gate.

Smiting scene on the palace side of the Window:

Smiting scene on front of Window:

However, they are absent from the 16 such scenes found on the columns that stand in front of the Window of Appearance in the first courtyard and are also not worn by the monumental images of the smiting king found on the front of the first pylon.

Columns in front of the Window:

Scenes of the king offering to the gods while wearing sandals are relatively uncommon. Of the 524 such scenes, pharaoh sports sandals on 62 occasions (11.6%) with 20 of these being related to the presentation of battle spoil. Other offerings presented while wearing sandals include incense, water libations, flowers, and more rarely, cloth, lettuce, and wine (these last three only once each).

One of the more interesting patterns deals with scenes of the king offering Ma’at (or a rebus of his name styled as Ma’at).

Barefoot king offering Ma’at:

Although there are 62 examples of this type of offering at Medinet Habu, he only wears sandals in six of them (9.6% of the Ma’at offering scenes) and these are all found on the East High Gate.

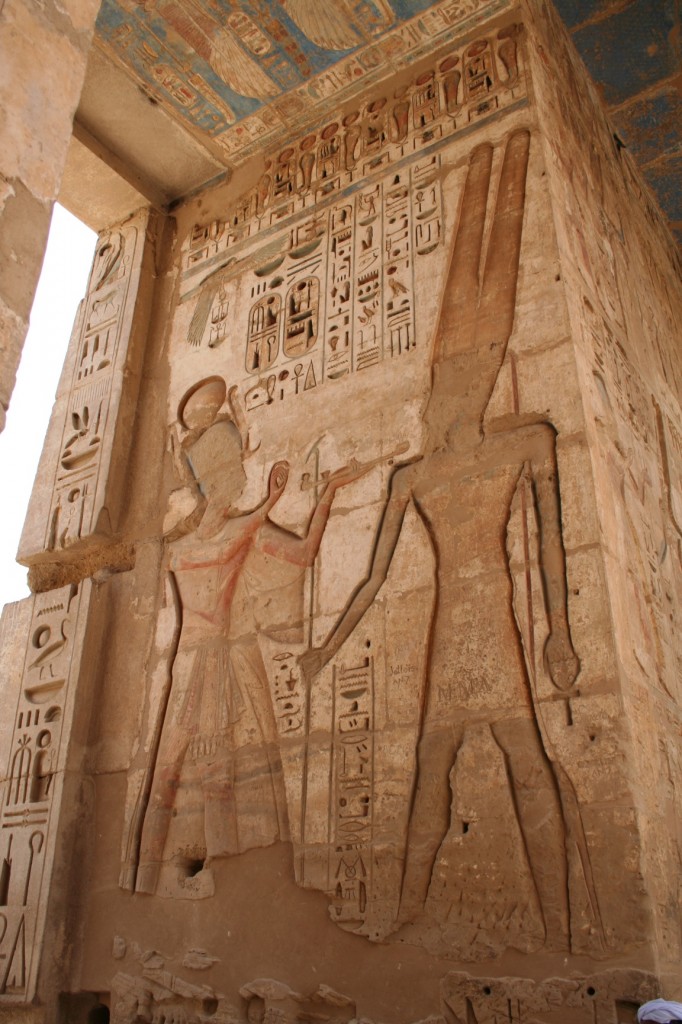

General view of the East High Gate:

Bringing it all together

This basic survey of the usage patterns for sandals being worn by the king has highlighted the fact that there definitely are usage patterns, even if the precise reasoning behind some of those patterns are not yet clear.

Although this survey has revealed quite a bit about the broad usage patterns of sandals as royal regalia, some of the specific patterns are less defined. Why, for example, does pharaoh wear sandals in only 5 of the 58 scenes at Medinet Habu where he offers vegetation (once lettuce, four times flowers) to Amun-Re and to Atum? Why those particular scenes? Why, of the 62 instances where the king presents Ma’at (or a rebus of his name styled as Ma’at) does he only wear sandals six times, and all in the East High Gate? There are two Ma’at offerings in the Gate where he is barefoot, so it isn’t just about the location—there are seem to be other variables at play here. Part of the reason for the obscurity in terms of the statistical analyses performed here has to do with the current size of the dataset, due to its being focused exclusively on a single monument. With the planned expansion of the database to include many monuments and objects from all eras, these and other patterns should come into sharper focus. It is hoped that more systematic research of the appearances of sandals on the king’s feet utilizing the quantifiable methodology developed for this project, combined with broad collaboration and the vast expansion of the database, may uncover deeper subtleties of meaning connected with the sandals that are currently obscure.

However, the data from the Medinet Habu study still has plenty to say about royal sandals:

- Sandals were not just worn to protect the king’s feet in the physical world, but were also considered appropriate to enlist for this function in other contexts. Sandals were worn by the king in all sections of the temple, although the proportion of scenes in which they appear differ greatly. For example, in the East High Gate, sandals are worn in 45 scenes and excluded from only 10. In the second courtyard, however, the king wears sandals 11 times and is shown barefoot in 200 scenes. This basic frequency data demonstrates that there was a different decorum at work in the design of the royal costume in various parts of the temple.

- There is a very close connection between sandals and scenes that show the king dealing with battle spoil, whether receiving it from his troops or presenting it to the gods. Every time the king is shown being presented with spoil (where it can be determined), he wears sandals. Similarly, of the 23 scenes that show the king presenting battle spoil to the gods, only 3 of them clearly show him barefoot. Two of these appear on the exterior north wall and the other is the prominent scene found in the first courtyard on the east face of the south tower of the second pylon.

- Sandals are intimately related to scenes where the king processes among humans. They are definitely worn in 17 of the 28 such scenes, and are only clearly not worn in 3 of the 28 (the remaining examples being damaged beyond determination). These three scenes are all processional moments from the Min and Sokar festivals (depicted on the walls of the second courtyard)—the single processional scene from the Min festival, and two of the three such scenes from the Sokar festival. The absence of the sandals in these particular moments of the festivals is especially interesting since the sandals are definitely worn in all but two of the scenes from the Min festival and half of the scenes from the Sokar festival.

The data therefore suggests that sandals were considered essential for separating the king from the terrestrial plane when he was engaged with it.

There are 127 scenes at Medinet Habu that include other humans besides the king. Of these, only 26 clearly show that the king is not wearing sandals. Eighteen of these are smiting scenes—on the exterior of the first pylon and the columns in front of the Window of Appearance in the first courtyard. Three scenes of the king presenting battle spoil, including prisoners, show him bare foot, and two scenes in the royal mortuary complex show the king seated and barefoot being treated as a divinity. The remaining three scenes are the Min and Sokar processions mentioned above. These public moments of a divine festival perhaps required that the king emphasize his role as intermediary between the terrestrial realm of his people and the cosmic plane of the gods by physically connecting with the processional pathway.

Min procession:

Sokar procession:

Conversely, of the 609 scenes where the king interacts solely with the gods, he wears sandals on his feet on only 53 occasions. Forty-five of these 53 are scenes of the king presenting an offering to the gods. Two are found on the exterior south wall of the temple, connected to the great calendar inscription. The colossal scene of the king offering incense to Amun within the portal of the second pylon shows the king wearing sandals, as do most of the offering scenes connected to the Min and Sokar festivals.

Portal of the second pylon:

Offering scene at beginning of Sokar festival:

Offering scene at the culmination of the Min festival:

It is noteworthy that sandals are worn in five of the offering scenes from the treasury, where the king presents material battle spoil—bags of gold, piles of metal rings, and ingots of copper. With the exception of the very unusual deshret crown combined with shwty feathers worn in a bouquet offering, these scenes in the treasury are the only places where the crowns related to Upper and Lower Egypt are paired with the sandals at Medinet Habu.

White crown worn with sandals in the treasury:

Red crown with shwty feathers worn together with sandals in an offering scene in the hypostyle hall:

Nearly half (20 out of 45) of the offering scenes show the king presenting incense, most of the time (14 instances) in conjunction with water.

Incense and libation offering:

There are several scenes showing more unusual offerings, including the aforementioned treasury scenes and one each of cloth (occurs 4 times at Medinet Habu) and lettuce (which appears 9 times total at Medinet Habu). Thirteen of the offering scenes appear on the East High Gate: one on the east face, six within the portal passage, and six around east face of the portal opening. As mentioned above, six of the offering scenes found on the Gate show pharaoh presenting Ma’at or a rebus of his name styled as Ma’at. The other offerings include incense and libations, bouquets, and wine. The wine offering scene is the only one of the 101 such scenes at Medinet Habu where the king wears sandals.

Besides the offering scenes, pharaoh wears sandals in a scene found in the room between the towers of the first pylon where Ramses praises the ascendant Re-Horakhti. The remaining seven scenes all show the king being led to receive emblems of kingship or is depicted receiving them from the gods.

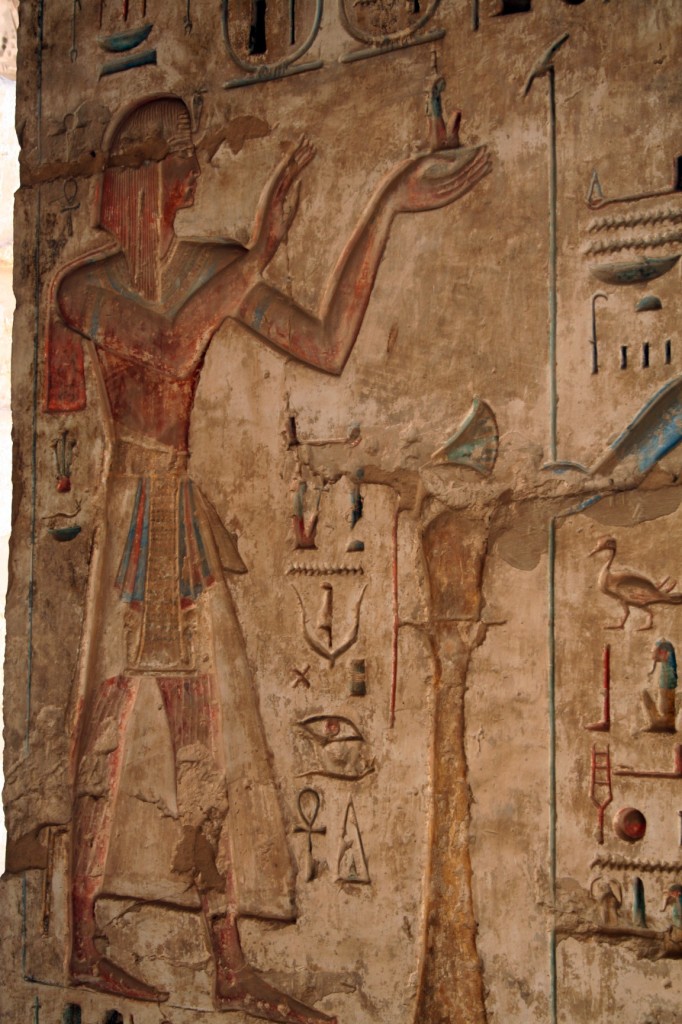

Ramses being led while wearing sandals:

Ramses receiving jubilees while wearing sandals:

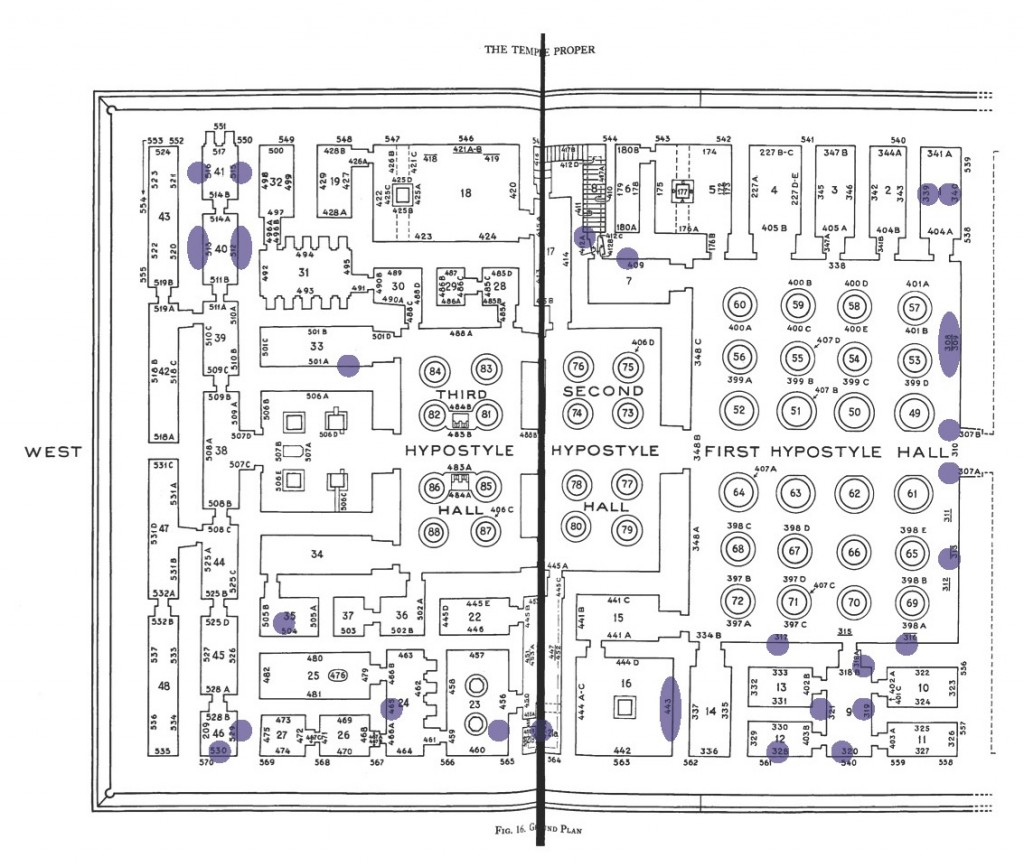

Within the temple proper, sandals are worn in the following venues (Room numbers refer to those of the Oriental Institute expedition):

- The chapel dedicated to the cult of the living king (Rm 1).

- The walls of the first hypostyle hall and flanking the portal from the second courtyard.

- In the treasury, specifically framing the hall (Rm 9) that leads to the four storerooms.

- In the bark shrine dedicated to the Amun of Medinet Habu/deified king (Rm 7).

- In the chapel adjacent to the bark shrine dedicated to Montu (Rm 16).

- Within the royal mortuary complex, in two scenes in the outer rooms, and one located between the doorways to the inner chapels (Rm 24).

- In the bark shrine dedicated to Khonsu (Rm 33).

- In the chapel adjacent to the bark shrine dedicated to Mut (Rm 35).

- Within the inner sanctuary dedicated to Amun (Rms 40, 41, and 46).

Many of these contexts are places that could arguably represent a conceptual intersection of the terrestrial and divine realms and might help explain the use of sandals in these venues. For instance, the scenes in the hypostyle hall that include the king wearing sandals depict him being led to receive the rights of kingship or show him being endowed with jubilees, representative of a long reign. These actions, which transformed the living, human man that was pharaoh into a semi-divine being that embodied the eternal ka of kingship, can be viewed as occurring in a liminal or transitional zone linking the terrestrial and celestial realms. Similarly, the scenes of the king presenting battle spoil to the gods can be seen as conceptually bridging the gulf between the realms, controlling the chaotically foreign and bringing it in line with Ma’at. By wearing sandals in these venues, the king is able to interact with the divine without the risk of tainting them.

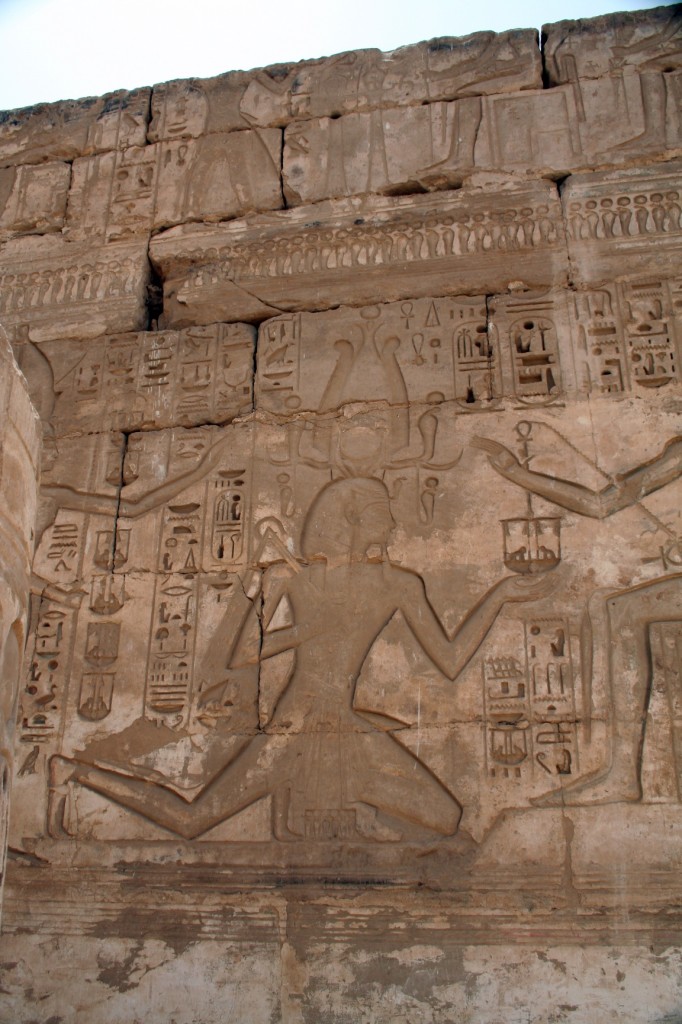

This seems particularly the case with the scenes that occur in the inner sanctuary.

South end of the suite of rooms:

These rooms, hidden behind the central bark shrine of Amun, were considered to be of great importance. The series of scenes show the king offering to several different forms of Amun, including a lion-headed primeval form, a mummiform Amun, a falcon-headed Amun-Re-Horakhti, and an ithyphallic Amun.

Ramses offering to a lion-headed form of Amun:

Ramses offering to a ram-headed mummiform of Amun:

Ramses offering to an ithyphallic form of Amun:

Ramses wears sandals in six of these offering scenes at the northern end of the suite of rooms and in two found at the southern end. In this context, the king might wear sandals specifically to prevent his inherent humanity from introducing a chaotic element in this ‘holy of holies’, which was designed to be a perfected, safe venue for the gods to inhabit.

The data therefore suggests that, although it was not common for the king to wear sandals in the presence of the gods, he did don footwear in those contexts where he represented a conceptual bridge between the terrestrial and divine realms and in those venues where it was especially important that the sanctity and purity of the divine be protected.

This study of the use of royal sandals at Medinet Habu has provided a peek into the usage patterns of this regalia element within the context of the king’s mortuary temple. As might be expected, the king almost always wore sandals when he interacted with other humans. However, the few scenes that show him barefoot among his subjects, the processional scenes from the Min and Sokar festivals, demonstrate that the footwear could be excluded from the king’s costume in certain situations where he was acting as a conceptual bridge connecting his people to the divine realm. The data from Medinet Habu also shows that although the king rarely wore sandals when he interacted exclusively with the gods, he did sport footwear in those venues where he was in a transitional zone, spanning the gap between the terrestrial and divine, or in those special places (like the Amun sanctuary) where his inherent humanity could conceivably allow chaos to enter an idealized, perfected portal that connected the realms and bring danger to the gods.

Amazing pictures and study of this old civilization. Even though the customs are old, the same basic ideas exist today: leaders take spoils from their people, prisoners, and enemies and worship false gods. I see it today, too, here in my own country and around the world. I am a servant to my leaders, giving them gifts in the form of taxes. If I make my leaders upset by breaking their rules, I could be persecuted, sent to prison, or murdered. Instead of beheading, our leaders today electrocute or inject lethal chemicals into our blood. In the Egyptian art you show, I am one of the peasants offering grains to our leaders. Instead of real grain, I am giving taxes. But in my heart, they are not my leader.

What do you think today’s analogy would be for the footwear? What do our leaders wear or display that is analogous to the sandals? I wonder if it is possible to know because our leaders do things behind closed doors without letting us see their secrets. The future may reveal to you what today’s leaders are doing behind closed doors.

Thanks for sharing your pictures and study!

Thanks, Earl, I’m glad you are enjoying the site and the research we are doing!

As far as modern analogies, footwear is still significant when you think about it, but modern rulers also use more overt displays. Mubarak’s now famous ‘name suit’ is a perfect example.

You are definitely right; some things never change.

Thank you for commenting!